There is something mesmerizing, yet indescribable about New Orleans. For as many times as I have been, I still don’t understand it. Yet, it’s one of the American cities I enjoy most. Whether it’s folks calling me “baby” or the ever-present Bounce remix thumping from sound systems worth more than the vehicles they’re in, ain’t nothing like New Orleans. Then, there are people like Welmon “Uncle Shadow” Sharlhorne, local legends whom you unintentionally meet on street corners in a barroom overflow during an afternoon siesta.

Meeting “Uncle Shadow”

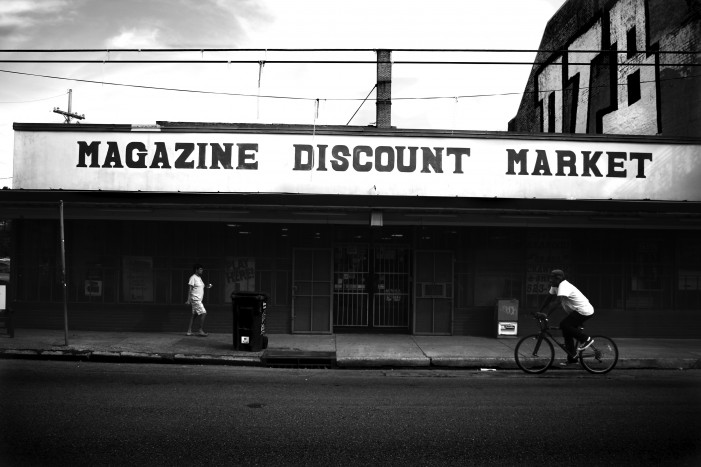

Generally when I go to the French Quarter, I, like most visitors, largely hang around Jackson Square. There are racist landmarks, famous donut-like eateries, farmer’s markets, and local creatives showcasing arts and talents. For me, my favorite second-hand book store—and at least the second-best Eggs Benedict—in the Crescent City are there. However, instead of beelining it to the square I tried to spend more time wandering the streets north of Decatur…and this is how I met Welmon.

While walking down what seemed to be Antique Row, I stumbled upon the Chart Room, a cash-only dive bar on the corner of Chartres and Iberville. From across the street—thumbing through photos and calculating the direction of my next move—the place looked largely empty. But it’s New Orleans, of course, so there were a few folks gathered around the bar. It seemed like the type of place where, although there were options, you’d be better off ordering a beer or whisky to avoid the screech of a skipping record and being politely told to take your new, big city sensibility for hand-crafted cocktails and “fuck off.” Still, others sat in green vinyl benches huddled along the back wall less than a foot away. Nearly halfway out the French doors, casting shadows on the sidewalk, were a hodgepodge of three wooden chairs losing their varnish. Seated in the middle, an elder; he was the most interesting—if not also peculiar—man I’d ever seen in New Orleans.

At first glance, he seemed like any other patron, slow sipping “cola” through a straw from a plastic bar mug. He wasn’t impeccably dressed or drawing attention to himself in any observable way. Nevertheless, he had a particular style and the palpable presence of an ornery Black man with stories to tell. His hat was dark grey, suede, with a black satin ribbon at the bond. Possibly salvaged, his eyeglasses wore like hand-me-downs—chipped and peeling, missing both lenses and begging questions our brief encounter would not afford the time to ask. His face was aged, hard. Perhaps from the 22 years better spent following dreams Black boys dream, but instead were spent behind bars at Angola—a state prison facility full of Black dreams deferred.

Under a lightly-wrinkled plaid Oxford, which was buttoned fully through the neck although the collar undone, rested an average frame sluggishly leaning against the chair back. Against his shoulder, a cane like nothing I’d ever seen before. At this point, my staring was obvious. Welmon, gesturing with his hand like a grandfather requesting the ‘mote control from the top of the TV, ushered me over. What began was an otherwise unsolicited, first-person whale tale on Welmon’s part in which he, among other things, effortlessly called me “boy” while simultaneously carrying on about his recent sexual exploits and catcalling a passerby. Pointing toward his cane, which I was already decoding as it rested on the arm of a nearby chair, he said, “I made that, you know.” Welmon then proceeded to explain the cane’s story, one whose details I can only vaguely remember.

A combination of salvaged materials, which included an assortment of beads, fluers-de-lis, and crosses, Welmon retraced his conversation piece, telling me what I can only summarize as a rather tragic story of a black boy coming of age in Louisiana. Between the intermittent placement of two Buffalo nickels were figures of small children, babies really, whom despite the cluttered experiences depicted before and after were over and again saved by God’s grace. Near the foot of the cane, however, was the segment of a spoon, the neck partially bent and the bowl blackened from direct heat of addiction. “I’m famous, you know,” Welmon said. “Look me up, I’m an artist. I got art all over the place; that woman across the street wants to meet me” he continued as he pointed his half-smoked cigarette toward a nearby gallery.

Sure enough, Welmon Sharlhorne, also known as “Uncle Shadow,” was both myth and legend. His artwork, largely ink drawings done with pen, had been placed in the Smithsonian and National Museum of Art in New York. I don’t know if I was more surprised by Welmon’s story, or his impeccably clear diction for a man with no teeth. “You know what I need, boy?” he asked me. Looking at the tread of his shoes, I could think of a few things, but I simply replied naively, “No, what?” Then, smooth yet quite matter of factly, Welmon again leaned back in his chair and said “If you got five dollars, I could use that to get off this corner and catch the bus.” I couldn’t knock the man’s hustle, hell. So, I reached in my pocket and gave him a Lincoln, which he then placed in his breast pocket before shaking my hand and saying, “Thanks, young buck.”

Shortly after, others had stopped on the corner and gathered to admire Welmon. The enthusiasm bursting through his smile of lip wrapped around gum, he proceed to “talk jive” and reminisce of nights long gone. His tall tales of Decatur’s misgivings abounding, I slid out past the small crowd to capture of Welmon what I could. I had planned to sneak a few pictures earlier, when I first saw him, but it felt intrusive, impersonal, and culturally inauthentic. Somewhere between having sat with him to learn and listen and the growing presence of other strangers lay the mask of a guilty conscience for my artistic curiosity. In that moment, I could effortlessly make a muse of the life of a Black someone, the “Uncle Shadow” I barely knew.

Photogallery

As Tom Robbins wrote in Jitterbug Perfume, “New Orleans,” with its brackish waters and softly salted air, “listens eagerly to the seductive promises of the future, but keeps at least one foot firmly planted in its history, and in the end, conforms, like an artist, not to the world but to its own inner being–ever mindful of its personal style.” It is as if there is no other way to define New Orleans but through its own colloquialisms, idioms, and other cultural merits. To be a visitor, however frequent, is a perpetual experience of finding and being found: in every Cajun bite and nibble, hoodwink and hustle, sidewalk F-sharp and B-flat, and at the bottom of empty bottles shared between once strangers-turned-momentary friends. In these ways, New Orleans is almost always unchanged for the sojourner trapped in nostalgia. But with each visit, a new wrinkle of complexity and nuance is added to the memory of a place both a free spirit and empty stomach can love. There’s simply nothing quite like it, New Orleans, which is why I always return.