If you watched last year’s MTV Video Music Awards, where Beyoncé received the coveted Video Vanguard Award, you will know that Laverne Cox had a better time than anyone else. During Beyoncé’s flawless 16-minute performance, Cox was dancing, singing along and being an endless source of “yaaaaaaaaaaasssss” memes. Reading South African author Rebecca Davis’ book Best White and Other Anxious Delusions made me feel a little like Laverne Cox at the VMAs.

2014 was audaciously declared The Year of the Essay, a form that still seems to be having its “moment” in popular culture. Books like Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist, Megan Daum’s The Unspeakable, and Mindy Kaling’s Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? have both popularized and drawn on the zeitgeist of the current literary moment, spending months on bestseller lists.

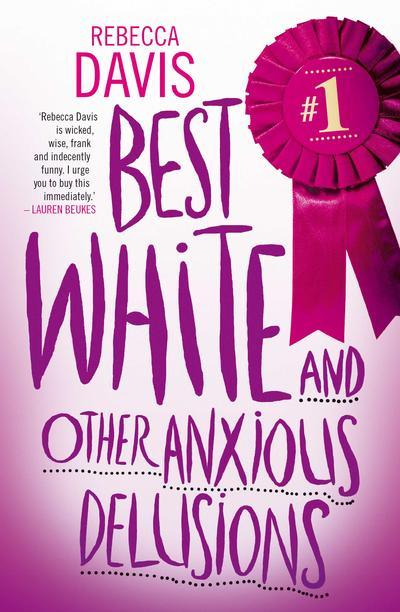

Essay collections often weave humor, memoir, pathos, and social commentary into a form that unapologetically centralizes personal experience and revelation. It is in this tradition that Rebecca Davis’ new book, Best White and Other Anxious Delusions, makes its entrance, part of a literary landscape that is often scarcely populated in a South African context, where collections of columns are generally more popular.

I came to this book expecting a collection of political columns, tinged with her signature wit. Instead, the book is a range of witty essays underscored by sharp social and political commentary—and is all the better for it.

Essayist Roxane Gay opens a piece on Daum’s collection making an unlikely yet apt connection between the work of the essayist and the lyrics of “Poetic Justice” by Kendrick Lamar, writing:

In the song “Poetic Justice,” Kendrick Lamar raps, “You’re in the mood for empathy, there’s blood in my pen.” This is how we might consider the essay—blood in the pen of the essayist, inking the personal to bring about an empathetic response.

In Davis’ instance, the essay goes beyond evoking empathy, being provocative, revealing the humor in the everyday, and inviting critical thought.

If you are familiar with Davis’ work from her Daily Maverick and Sunday Times television columns and Twitter feed, or know her personally, like I do, you will be aware of her skill at sharp, incisive social commentary, housed in her signature self-deprecating, humorous style. Through this style, the line between the personal and the public is always neatly drawn. Humor acts as a distancing mechanism in her work: enough is shared for Davis to emerge as three-dimensional, interesting, and hilarious, but as much is held back.

The chapters form a tightly-knit collection of concise opinions on varying topics. They range from exploring the art of the high five, love in the time of the internet, and the problems with the Goldilocks fairy tale, to mansplaining, Kindles, and more. Davis manages to make opinions on the ostensibly mundane and the political in the everyday feel fresh, unique, and relevant. The four-to-eight page length of the chapters gives you space to breath between topics, making the book digestible and easy to engage with. This is not the book equivalent of a greatest hits album, churning out opinions that we are familiar with, but rather a playful, insightful and fresh engagement with a range of topics that speak to the South African zeitgeist, but resonate beyond it.

Davis manages to make opinions on the ostensibly mundane and the political in the everyday feel fresh, unique, and relevant.

At times, ideas were touched on that felt like they needed further unpacking. This probably speaks volumes about my conditioning for the explanatory breath that columns allow, and familiarity with Davis’ long-form political and social analysis. Our critiques, and their language for making sense of the word, can often reflect as much of ourselves and our worldview as the site of our critique itself. Once you settle into the essay form, however, you appreciate these nuggets for what they are—not wanting them to be bent, stretched, or molded into any other, longer form.

The “Best White” chapter, a satirical sketch of new South African white liberals who are in an imaginary competition with everyone else—a kind of anti-racism pageant—feels like it needs its own television show, with Davis as its Tina Fey-esque head writer. The book often feels like it has the same delivery and razor-sharp finesse that Fey’s show 30 Rock was known for, smartly navigating our South African sense of place or dis-place, comfort or discomfort, and politics right now.

In “Mansplain That to Me Again,” Davis describes various scenarios “where a man takes it upon himself to explain a subject to a woman with the assumption that the woman cannot probably have the same degree of knowledge on the subject as a man.” She gives various examples of this phenomenon, to reveal how mansplaining is pervasive, exhausting, and a daily part of women’s lived experience. Familiar with the concept, I could not help feel that, in the words of Toni Morrison: “there will always be one more thing,” a need for countless examples that keeps people on the margins explaining their lived experience, and responsible for the burden of proof and receipts. However, she was preaching to the choir. The concept could be revelatory and enlightening to someone unfamiliar with it. The benefit of the many examples Davis gave is that it shows the subtle and overt workings, dynamics, and many layers of mansplaining, revealing how widespread it is across professions and experiences.

The “Best White” chapter, a satirical sketch of new South African white liberals who are in an imaginary competition with everyone else—a kind of anti-racism pageant—feels like it needs its own television show…

The chapter “Never Read the Comments” had me channelling my inner Awesomely Luvvie, and exclaiming “das realtalk right thurrrrr”—as someone who understands the experience and impact of online comment sections and the wide berth they require when you dare to venture into opinion writing. The link to Lamar’s “Poetic Justice,” “blood in the pen of the essayist,” is the clearest here, as Davis shares her experience and feelings about some of the harshest comments she has received—some of which have remained indelibly inked in her mind.

She artfully plays with the line between sharing and oversharing, using humor to achieve that distance, in a way that at times can achieve something similar to dramatist and director Bertolt Brecht’s vervreemdingseffekt: a distancing mechanism he used to make sure his audience remained critical and didn’t lose themselves in the narrative. Davis weaves essays that often make you think, at times through extremely subtle coercion, and at other times through pointed theorising of concepts and their effects, but never through shouting things at you. This nuance in the delivery is probably one of the best features of Best White.

With Best White, Davis allows us direct, subtle, and oblique glimpses into the personal, deftly navigating the revealing nature of the personal essay, her personal life, and public, online persona—which she comments is “braver, chattier and about a million times more confrontational than offline.” You gain insight into who she is and what she thinks, through the lens of an immensely subtle dance between her online persona and real life personality.

Davis weaves essays that often make you think, at times through extremely subtle coercion, and at other times through pointed theorising of concepts and their effects, but never through shouting things at you.

Her deft writing crafts commentary that is relatable, entertaining and clear, without losing or compromising the analysis. This book theorizes the everyday, sometimes simply making the mundane funny and interesting, and at other times showing how particular systems of privilege structure our lives, without grandstanding or jargon. She is constantly checking herself, firmly embedded in her critique, but this never feels laborsome or sacrifices on content or humor.

There are many possible challenges in writing a review of a book by someone you know, on any level. You can hate it and have to say you liked it, or feel completely apathetic about it (which can make your next encounter so many levels of awkward). Or you’ll love it, and have to prove it’s not because you know them. With this book, thankfully, the challenge is the latter – particularly the attempt to quiet my inner Laverne Cox, when all I wanna do is yell “yasssssss.” So consider these 1000-plus words the finite, unapologetic receipt for my exceptionally prolonged Laverne Cox-esque yasssssssss.

Yaasssssss, Rebecca, yaaaasssssss.