Once upon a time, I lived in Colombia. And one day, I posted this as my Facebook status:

Acabo de caminar del gimnasio. Hoy es un día brillante de sol tropical. Y bajo de ese sol iluminante, se me dió cuenta que yo era el único negro/moreno/mulato en la calle que no era obrero, vigilante, mulero, vendedor de cocadas o aguacate, o muchacho de servicio. ¿Qué vaina tan desesperante?

Translation:

I just walked home from the gym. Today is bright with tropical sun. And under that illuminating sun, I noticed that I was the only black/African-descended guy in the street who wasn’t a construction worker, security guard, mule driver, coconut treat or avocado seller, or servant boy. How depressing!

An immediate response from a FB friend:

Interesante, pero qué negro? Vos no lo sos o no pareces.

Translation:

Interesting, but what do you mean black? You’re not, or you don’t look it.

Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been plagued by the eternal question, “What are you?” I won’t lie and say that I’ve always had a solid racial identity, but for most of my 37 years, I’ve lived life as a black American male, albeit one of obvious mixed phenotype. Growing up in the American South, my identity was never questioned by whites, only by the other blacks I went to school with, often pointing to my curly ‘fro and calling to me in faux-Spanish, “catada-potodo” and all that jazz. My mother, herself the recipient of much vitriol from her darker-skinned peers during her years in segregated schools and at an HBCU in the late 1950s, told me how she had often been mistaken for white during the pale winter months of her youth. But despite her recent European ancestry and light-bright-damn-near complexion, she was born in 1938, under the equalizing rule of hypodescent in the United States, with the requisite single drop which once and forever placed her on the dark side of the color line. And it was under the same culture and climate of that rule that I was born in 1977, reddish-brown, darkening in summer, with features sitting halfway between two continents.

…what do you mean black? You’re not, or you don’t look it.

That did not mean, however, that I was raised culturally confused à la Diff’rent Strokes. I grew up in a black neighborhood, in a black Baptist church, in a black family with members “from coal to cream.” My youth was always a little bit Cosby, a little bit Good Times, a dash of 227, and a whole lot of Amen. I was surrounded by institutions of black middle-class success, not quite Atlanta-level entrepreneurial luxury, but the fruits of striving, college-educated Southerners who marched in high-stepping bands and continued to serve the Greek letter organizations they joined back when it meant something; and always within a ten minute drive of the ‘hood and the cheap Chinese take-outs and barbecue joints. I was a member of a black Boy Scout troupe and learned about W.E.B. Du Bois and Madam C.J. Walker and Charles Drew as a part of the McKnight Achievers Honor Society. Curly hair notwithstanding (gone now, actually), I grew up black. And I know what it means to be followed around in stores, to attend a high school with ’50s-era library books, and to be harassed by the police.

I’ve come to reconcile my phenotype the way I reconcile my interests, that to be black—physically, culturally, emotionally, spiritually, politically—is not to be monolithic. That we are, in every range, dimension, and manifestation imaginable. It took me going through stages of emotional maturity, attending a mostly-black high school (where I was hated for being a fat Oreo nerd) and an HBCU (where it was finally cool to be smart, diverse, and culturally inquisitive), and traveling through the realms of my brothers and sisters in the Diaspora, most notably Latin America (where I initially had the naive expectation that people who looked like me also thought like me).

“Why you wanna be a black nigger?”

I was asked that once by a Colombian woman who had lived for a while in the United States and couldn’t get her translation right; Spanish subtitles for American movies and TV shows give negro for both “black” and “nigger.” Though I’m sure she was educated in the proper derogatory terminology during her time in New York. Anyway, her question was prompted by my response to her original query of whether or not I was Latino (that catch-all term which incorporates Spanish-speaking cultures from Mexico to Argentina and truly means absolutely nothing outside of an American cultural context, and even then…), something often asked of me. My answer is always either negro americano, afro-americano, or a mix of the two. More often than not, this answer is never accepted at face value, hence her perplexity at why I would choose to identify myself as something A) seemingly unpleasant, judging by her tone and facial expression, and B) apparently untrue.

“Why you wanna be a black nigger?”

See, in Latin America, the race issue is less, pardon the pun, black and white than it is in the U.S. The Spaniards and Portuguese, already a mixed lot, had much less reluctance than their British counterparts in planting their seeds in foreign soil, so to speak. In fact, an entire range of interesting names developed to accompany the corresponding array of skin tones, hair textures, and facial dimensions, the most prevalent being mestizo (white/indigenous), mulato (white/black), and zambo (black/indigenous). Along with this color gradation came social value, rated according to your position: African slaves, invariably, at the bottom. Underlying this system was the exact opposite idea of hypodescent—one drop of any other blood kept you from being black (though not necessarily enslaved), and some places even allowed enterprising mixed-bloods to purchase whiteness (I can provide a bibliography and syllabus upon request for the incredulous among you, dear readers). Wrap all this in the typical European colonial social matrix that privileged whiteness above all else (repeated throughout the Americas, Africa, and Asia), and you can understand why no one in their right mind would actually choose to be black in Latin America if they didn’t have to. Why would anyone want to identify with a group of people who, still in 2015, maintain the lowest position on the social ladder in the countries where they are greatest in number, and whose color is a euphemism for poor, dirty, and ugly? Where a Spanish word for cute (mono) is default for blond and where one “German” or “Spanish” grandfather is enough for people who look like Denzel or Oprah to claim, “I’m not black, I’m mulatto,” as if that were a badge of honor (of course, there are no Colombian Oprahs or Denzels because maybe they don’t want to be on TV or in movies in Colombia, right?).

It’s this same lack of identification that keeps the colonial structure in place, because there’s not enough unity or anger to incite any type of focused paradigm shift reminiscent of the American Civil Rights Movement. The segregation there is most certainly economic, but that functions as a proxy for race when the majority of the lower-class, with no access to adequate education or jobs, is indigenous or of quite obvious African-descent, and the number in the upper classes is negligible (of course, everybody always seems to know the one exception that proves the rule). And people here tend to think that their mixed-raced societies indicate the lack of racism; I’ma tell you that fucking your dusky, voluptuous maid (or paying her to deflower your 15-year-old son) is not the same as legitimate socioeconomic mobility.

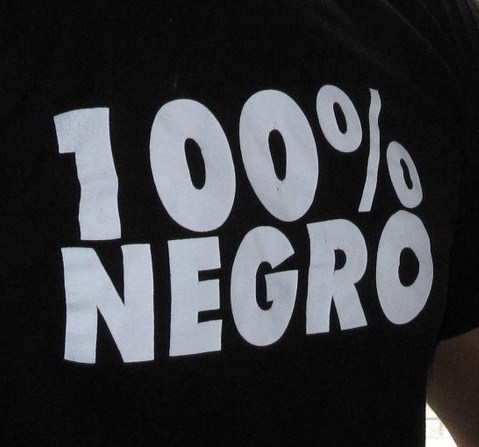

100% Negro

In Colombia, and in many conversations with people from Latin America, I was called racist for even talking about race, and for pointing out inequalities that had theretofore gone unnoticed. I was called divisive and off-putting for being proud of my own heritage by people who think nothing of invoking their Italian or German or Norwegian ancestry. I even had a fellow professor once ask, exasperatedly, if we had to talk about race on a Friday afternoon just after I discovered a student had included “nigger” in an academic paper! (Must be nice to have the luxury of scheduling life’s inconveniences, you douche). Still, people can call me any number of things, but it doesn’t reduce the ingrained responsibility I feel for educating and raising the consciousness of my own people as well as others.

I was called racist for even talking about race, and for pointing out inequalities that had theretofore gone unnoticed.

When asked why I care so much, I answer that it is because of sheer luck and cosmic grace that my ancestors’ slave ship docked in Charleston and not Cartagena, Santo Domingo, Kingston, or Salvador. Because the United States proves over and over, despite severe and deeply-ingrained problems, that it is, in my opinion, the only country in the hemisphere (along with Canada) where people of African descent have a decent shot at unfettered success regardless of skin tone, last name, foreign parentage, or bank account balance. And like the Afro-Colombians, Dominicans, Jamaicans, and some 90 million Brazilians, to name a precious few, I am the descendant of Africans brought over to the Americas as property, speak a European language, and have been acculturated to European mores and values. The language may be different, but the history and heritage unite us. That is why I care about what becomes of a bright 12-year-old black kid who has to stop school to sell chewing gum on the side of the road in Barranquilla to help his mom pay rent. That is why I care about what becomes of the 20-somethings who should be studying law instead of selling their bodies to the highest bidder at the clubs in Rio. That is why I care about what becomes of the Caracas street pharmacist with the business acumen of a Fortune 500 executive. Because under a different set of circumstances, they all could have been me.

There are varying levels of black consciousness throughout Latin America, with Cuba leading the pack and Brazil, Panama, and Venezuela at least showing up to the conversation. But there is still a huge dearth in the number of socioeconomically successful Afro-Latinos/negros/morenos/mulatos/whateverthehellyouwannacallem to serve as examples for younger generations to aspire to, or for non-blacks to see as proof of a people’s abilities. So I willingly accept it as my duty to be an example to my people in the Diaspora, regardless of language or nationality, that black does not have to mean poor and uneducated and ugly (or shoe-leather dark).

My aim is not to pit groups of people against each other; it is to instill sufficient pride in a marginalized and victimized group of people to have them demand better for themselves from themselves, their governments, and their communities. To insist on equal opportunities for quality education and employment, and to see their broad features, kinky-curly hair, and dark skin as signs of resilience and fortitude, not something deficient and needing to be “improved” with each successive generation. I’m young, gifted, and black. I’m black and beautiful. I’m black and full of flavor. I’m black and proud (and uppity to boot!). And I want them to know what it means to be black like me.