In 2008 candidate Barack Obama campaigned with the slogan “Yes We Can!” When he became president in 2009, many thought he would be a transformational president. Soon however, it became apparent that Obama would face recalcitrant and racist opposition from both the GOP and the insurgent Tea Party in 2010.

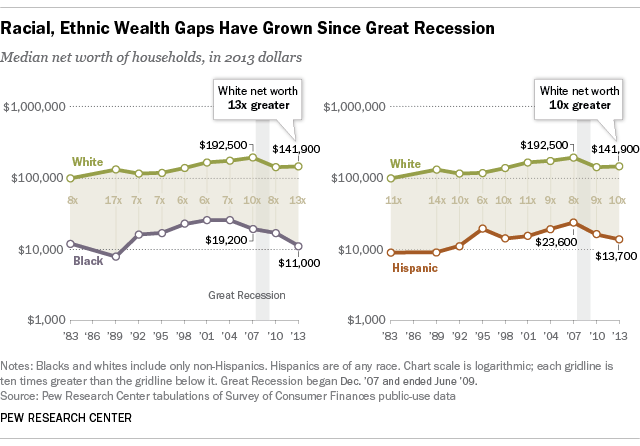

Looking back over the past eight years, we can assess the level of Black progress during the Obama Era. Using the data table from the Pew Research Center below, we see that the Black-White wealth gap grew under the Obama presidency, from a 10 to a 13 fold gap. While Whites have gained ground on their net worth after the Great Recession of 2008, Black folks have steadily lost ground and have not recovered.

In large part, the wealth loss after the Great Recession was due to the mass foreclosure crisis that disproportionately affected African Americans. The Great Recession itself was caused by banks’ subprime predatory mortgage lending to African Americans and other non whites, and African Americans were devastated disproportionately by mass foreclosures. Additionally, according to the Haas Institute’s report Underwater America, the underwater mortgage crisis was disproportionately concentrated in Black and Latinx neighborhoods.

Before the beginning of 2014, most of President Obama’s actions were race neutral (i.e. the Affordable Care Act and stimulus efforts to save the economy and spur job growth). In May 2013, President Obama delivered the commencement speech at Morehouse College, in it he stated:

My job, as President, is to advocate for policies that generate more opportunity for everybody. We’ve got no time for excuses—not because the bitter legacies of slavery and segregation have vanished entirely; they haven’t. Not because racism and discrimination no longer exist; that’s still out there.

Nowhere in his speech did Obama suggest that it was his job as president to help ameliorate the racial segregation that still persists in many urban areas. Nowhere did he say it was his job to pass policies to combat racism and discrimination in the form of redlining, sub priming, racial profiling, or disparate sentencing.

But that all began to change after George Zimmerman murdered Trayvon Martin on February 26, 2012 and was acquitted on July 13, 2013, just two months after his Morehouse commencement speech. In the aftermath of the Zimmerman acquittal, President Obama responded with executive actions to boost the life chances of Black, Latino, and other boys of color with his presidential initiative My Brother’s Keeper, announced on February 27, 2014.

Other presidential race conscious action would follow from Black trauma and grief:

- The police killing of Mike Brown by Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014

- The ensuing Ferguson Uprising in August 2014

- The police killing of Freddie Gray by Baltimore police on April 19, 2015

- The Baltimore Uprising on April 27, 2015

- The lead poisoning crisis in majority-Black Flint, which became a national story in January 2016

In response to these and multiple other high profile police killings and jail custody deaths of Black people, insurgent protesters from Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives organized militant direct action protests in cities around the nation. In Ferguson, Baltimore, Baton Rouge, Milwaukee, and Charlotte, uprisings erupted. These events spurred the Obama Administration to take even stronger action to make Black lives matter.

After viewing the highly militarized response of police to protests in places like Ferguson, President Obama announced a ban on some of the weapons police departments receive from the Pentagon via the 1033 military surplus program. Under Obama, the DOJ kicked into high gear and began to investigate Ferguson, Baltimore, and Chicago police departments. Both Ferguson and Baltimore reached agreements for consent decrees to help reform their police departments in 2016 and 2017, respectively. In October 2016, the federal agency SAMHSA disbursed $38.6 million in ReCAST grant funding to help cities recover from uprisings and build resiliency to trauma. Government agencies in areas such as Chicago, Flint, St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Baltimore were recipients.

In January 2016, President Obama declared a state of emergency in Flint, Michigan, clearing the way for federal funds to help mitigate the impact and damage of lead poisoning experienced by city residents. On January 13, 2017, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) released its final rule, lowering the threshold for lead poisoning to the CDC’s level of 5mg/dL.This means that nationally more children will be able to receive treatment and services for lead poisoning.

In addition, in the summer of 2015 HUD released its final rule for affirmatively furthering fair housing to tackle the persistent issue of racial segregation. Perhaps they realized it was no coincidence that many of the cities experiencing crises and urban uprisings were among the top eight hypersegregated metropolitan areas, as defined by Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey. These top eight areas are: Milwaukee, Cleveland, St. Louis, Baltimore, Detroit, Flint, Boston, and Birmingham.

As a result of these initiatives, there was some Black progress during the Obama Era in the following areas: boosting police accountability, demilitarizing police agencies, addressing trauma and lead poisoning, and fostering racial desegregation. Still, we must be clear that pro-Black presidential action came AFTER Black suffering, protests, and uprisings.

This is not a new phenomenon. The three great Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s also became law in response to tremendous Black suffering, protests, and uprisings. The 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were passed by Congress and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson only after more than six years of Black bus boycotts, mass protests, sit-ins, and other direct actions. Both of these bills were ushered through Congress after the terrorist attack and bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963, which resulted in the deaths of four precious Black teenage girls: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act was passed by Congress and signed by President Johnson on April 11, 1968—just seven days after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the eruption of the Holy Week Uprisings in over 100 cities by Black people in response to King’s death. The open housing or fair housing bill, which Dr. King had championed, had languished in Congress for two years and showed no prospects of passage until Dr. King’s blood was shed in Memphis, Tennessee. Only after Black youth erupted in anguish after his assassination, setting the nation on fire.

In America, Black progress usually comes at a great price: Black death and suffering, Black protests, and Black uprisings. Just as the Civil Rights and Black Power movement spurred legislative action in the 1960s, Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives spurred executive action in the mid-2010s. Both eras ended in a tidal wave of whitelash against Black progress, just as the founding of the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacist terrorism erased the gains of Black Reconstruction after the Civil War.

Much remains undone at the dawn of the presidency of Donald Trump: securing safety from hyper policing, obtaining wealth in our communities, halting the advance of school resegregation, and action on hypersegregation. The election of Donald Trump represents the Neo-Confederate Nullification of Obama and Black progress, as the GOP has attempted to repeal the Affordable Care Act even before President Obama leaves office.

One thing is for sure—Black rights are only as good as what the government will enforce or what Black people are willing to vigorously demand with direct action. Just as the 1980s witnessed a retrenchment of Black progress obtained in the 1960s-70s, the ascent of Donald Trump augurs another era of whitelash. A valid critique of President Obama is that his administration responded with too little, too late. It shouldn’t have taken Black suffering, protests, and uprisings to spur him into anti-racist action.

Black progress is not permanent. But Frederick Douglass prescribes a path forward, as he reminds us:

Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. If we ever get free from the oppressions and wrong heaped upon us, we must pay for their removal. We must do this by labor, by suffering, by sacrifice, and if need be, by our lives and the lives of others.

The question now is: will we continue making our demands for power known with Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives in the Age of Trump? Or will we be beaten back by cyclical American whitelash all over again?