Kendrick Lamar didn’t make an album. Or at least not in the traditional sense. To Pimp a Butterfly isn’t an album you’re going to want to just throw on. Its shuffle play value is low. This is an album you revisit. It’s an album you sit with. It’s an album you study. Kendrick didn’t make an album. He recorded a thesis. Kendrick recorded the 2015 State of Black America for posterity. And he did it brilliantly. It’s accurate. It’s artful.

To Pimp a Butterfly opens with Kendrick laying the historical context of the American Dream. It highlights how Black America internalized capitalism as self-worth and instead bred self-hatred. Kendrick then takes us through a journey of trying to find happiness and failing. He paints a vivid picture of the depression that comes from being black in America, and then journeys back to self-discovery. Finally, it gives us a plan for looking forward.

To Pimp a Butterfly opens with Kendrick laying the historical context of the American Dream. It highlights how Black America internalized capitalism as self-worth and instead bred self-hatred. Kendrick then takes us through a journey of trying to find happiness and failing. He paints a vivid picture of the depression that comes from being black in America, and then journeys back to self-discovery. Finally, it gives us a plan for looking forward.

Kendrick recorded the 2015 State of Black America for posterity. And he did it brilliantly. It’s accurate. It’s artful.

The introduction to Kendrick’s thesis on the State of Black America, “Wesley’s Theory,” picks up exactly where Kendrick’s debut album good kid, m.A.A.d city left off with “Real.” The final track of gkmc calls into question everything Kendrick once viewed as self-affirmative. The hook on this song is a mantra repeated over and over: I’m real. I’m real. I’m really really real. It’s soothing. It’s something you want to believe. It’s hypnotic. It’s convincing. It’s of my highest recommendation that you stop reading and just vibe out while that plays.

Each verse on “Real” has Kendrick detailing how we’ve negatively internalized the American Dream by viewing the wrong things as proof of our self-worth. The first is a woman obsessed with material things: “You love red bottoms and gold that say ‘Queen’. You love handbag on the waist of your jean.” In the second verse, we see a man in love with street life and everything that comes with it: “You love fast cars and dead presidents owed/ You love fast women, you love keeping control/ Of everything that you love, you love beef/ You love streets, you love running, ducking police.” And in the final verse, we have Kendrick asking himself, and us, what’s the point? I should hate everything I do love. Should I hate living my life inside the club? …Hating all money, power, respect in my will. Or hating the fact none of that shit make me real.”

Kendrick does an amazing job not talking down to us on this. It could’ve easily been a #HotepTwitter, “I’m-super-deep-and-wear-bow-ties” type of verse. But instead, he essentially says, “I know all of this is true because I have the same problem. I think the same way. I thought the American Dream was going to be enough too.” By taking this tone, he aligns himself with us. He exposes his wounds so that we’ll believe him. He’s giving his references. He’s telling us where he’s from and where he’s been. He’s asserting his blackness.

What’s blacker than having your parents yell at you on the phone to bring the car back while you’re out with the homies over the smoothest beat they can step to? It sets him up nicely to be the person to give us this thesis on the state of our union in 2015. The outro angelically implores us, “Sing my song, it’s all for you.” And it sounds so endearing, we want to believe him.

And we do.

Introduction – “Wesley’s Theory”

The album opens with the refrain, “Every nigga is a star,” which sounds less like an affirmation and more like mocking propaganda when you consider the theme. Think of stars as the actual celestial bodies that they are. There are… a lot. Some of them get names that we know and others are sold on the internet for $20 if you want to impress your grandma or take your DM game to an entirely new and creepy level. To paraphrase my favorite Disney/Pixar film The Incredibles, “If everyone’s special, nobody is.” We might all be stars, but we can’t all be Stars. This is the beginning of Kendrick’s firm proclamation that the American Dream is the American Swindle.

“At first I did love you, but now I just wanna f*ck. Late night thinking of you, until I got my nut. Toss and turned, lesson learned.”

Kendrick admits that initially he fully embraced the idea of the American Dream, which meant embracing capitalism and the love of money. Eventually, he just wanted more—more things, more money. Finally he got rich and that’s when trouble starts. “Wesley’s Theory” is about the American Dream, the love of money, and the evil it brings.

In the first verse, Kendrick hilariously, but convincingly, raps from the mindset of someone too deep in love with money. It’s a satire that you don’t want to believe is satire because it would mean he’s making fun of a lot of the music we listen to. Also because it’s just such a dope verse. You don’t even want to think about it. You just want to hit your shmoney dance and enjoy it.

Kendrick’s character is in love with money. He’s in love with the feeling. You can almost see the shiny suits in the music video he’s acting out. It’s an entire verse about how when he gets money he’s gonna ball out. “Ima buy a brand new caddy on fours/ Trunk the hood up, two times, deuce four. Platinum on everything, platinum on wedding ring.” And while he’s spending all his money on cars and guns, improving the American economy, he’s going to go back to his own hood and use those guns. Kendrick’s juxtaposition of the effects of the American Dream on White America and on Black America is stark. While White America benefits from the improved economy, Black America is hurting. You can spend all you want and improve their pockets, but you end up hurting your own people. “Ima buy a strap. Straight from the CIA, set it on my lap. Take a few M-16s to the hood. Pass ‘em all out on the block, what’s good?” Thundercat beautifully comes in melancholically with “We should’ve never gave niggas money”.

Again, here’s Kendrick’s strong assertion that the love of money has negative consequences.

Dr. Dre makes a cameo on this track and adds in one more point about the American Dream—once you’re in it, you have to pay to stay. The American Dream costs more than it may be worth.

In the second verse, Kendrick takes on the persona of the American Dream as Uncle Sam and how he convinced us to not only wholly indulge in capitalism but also engage in this authoritarian idea of hating those who don’t. It was so easy to believe in it. The American Dream was ostensibly available to anyone who wanted it. Kendrick raps with this tone I can only describe as Oprah-esque. No, not like that. But this suspiciously benevolent tone.

Anything you want, you can have! What you want you? A house or a car? 40 acres and a mule? A piano? A guitar? Anything! See, my name is Uncle Sam, I’m your dog!

Kendrick using the 40-acres-and-a-mule language, a proposed form of reparations for black Americans for the horror that was American slavery, immediately makes me think of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Clearly none of us got 40 acres nor a mule. Why?

Because America has defaulted on this promissory note. America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check — a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now.

Uncle Sam (the American Dream) might have looked a certain way. He might have seemed to offer everything we could’ve wanted or dreamed. But the American Dream has a long history of being a swindle. This is only but one of the many times Kendrick will cite influential Black Americans such as Dr. King throughout the thesis. He goes on to allude to Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Kunta Kinte, and so on. That’s not even considering the samples and artists on the tracks. From Snoop to Thundercats, it’s black. This album is beautifully black. It’s authentically black.

“Pay me later! Wear those gators! Cliche and say fuck your haters!” Not only does the American Dream create paralyzing debt for us, we still think we’re better off and start to hate anyone who says otherwise. Anyone who isn’t as into material things and flash lifestyle is now perceived as a hater, even if they do have the same skin color as us. “Everything you buy, taxes will deny. I’ll Wesley Snipe your ass before 35”. After the American Dream’s hype of all the money we can have, which we probably won’t get, even if we do somehow get it, taxes will take it right back. Poor Wesley Snipes learned that lesson real quick.

But this is the world we live in. We all believe in the American Dream, to some extent. Let’s not pretend that we don’t. If Kendrick’s going to try to convince us that the American Dream is really an American Swindle, we need to see receipts. We were raised on this. We’ve spent our entire lives feeding into this. What happens after you spend your whole life preparing to become something and you don’t like what you see? This is the Butterfly Dilemma. Your entire life is about becoming something greater. Something beautiful. Something free. Gather your wind, take a deep look inside/ Are you really who they idolize? To pimp a butterfly.

For Free? – Interlude

If “Wesley’s Theory” establishes money as the root of all evil, “For Free?” shows the internalization of the idea that money affirms us and how it leaves us dissatisfied. “For Free?” unfortunately opens with the voice of a stereotypical, angry, aggressive, sassy ‘hood black woman just completely destroying a man verbally. She’s clearly assimilated and internalized the American Dream. If the man she’s talking to doesn’t have money, he’s worthless to her.

“I shouldn’t be fuckin’ with you anyway. I need a baller-ass, boss-ass nigga. You’s a off-brand-ass nigga. Everybody know it. Your homies know it. Everybody fuckin’ know. Fuck you nigga, don’t call me no more.”

Kendrick raps back at this unsatisfied woman, “This dick ain’t free! You looking at me like it ain’t a receipt. Like I never made ends meet eating your leftovers and raw meat.” In other words, he’s not giving her (or the American Dream) this work for free. While he’s frustratedly describing how hard he works to keep his woman happy, he’s also talking about the so-called black middle class here, working to make ends meet by eating the leftovers from the table. Kendrick frustratingly declaring, “This dick ain’t free!” is really the 2015 version of crying “I, too, am America.”

“Tomorrow, I’ll be at the table when company comes. Nobody’ll dare say to me, ‘Eat in the kitchen,’ then. Besides, they’ll see how beautiful I am and be ashamed—I, too, am America.”

In “I, Too,” Langston Hughes reports the State of Black America as well. While the American Dream has shunned Black America and forced it into a second-class status, we’ve only grown stronger. We were cocooning. Tomorrow, we’ll be at the table. Tomorrow we glo up. Tomorrow we become a butterfly. Kendrick continues his rant with detailing all the things he’s worked for to keep this woman/The American Dream. It ends with “Oh America, you bad bitch, I picked cotton that made you rich. Now my dick ain’t free.” Kendrick’s tired of working with no return on his investment. America gon’ pay what it owe.

King Kunta

“King Kunta” is about authenticity. The obvious allusion is that the classic black television miniseries. Roots, by Alex Haley, is based on the life of Kunta Kinte, a slave whose foot was chopped off so that he could not run away from his masters. The very term “King Kunta” is an exercise in hilariously defiant authenticity—juxtaposing the royal title “king” with the African name Kunta, instead of the slave name Toby. The scene most people remember from Roots is when Kunta is being whipped and told to accept that his new name is Toby. And he takes every brutal lashing and continues to assert that he is Kunta. His name is his name. And he’s not changing for anyone. He’s not going to diminish or hide his blackness in even the smallest of ways.

The first verse starts with an allusion to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. There’s a part in the novel where the protagonist smells yams on the street and it reminds him of home. He buys some and happily feels authentically himself again. His peers were shocked that he would do that because it was a mark of being from the South and that was shunned. But he remained authentically Southern black, despite the hatred. Here, “yams” is authenticity. “When you got the yams- (What’s the yams?) The yam is the power that be. You can smell it when I’m walking down the street.” Kendrick is so authentically black that you can tell just by the way he carries himself. Kendrick’s citing of many black Americans isn’t to be inaccessible. I believe Kendrick wants us to revisit and explore these poets, writers, orators, and heroes. He wants us to fall back in love with blackness. Bring back their authenticity instead of the watered down revised history we are often offered.

This interrogation of authenticity continues with rappers. “I can dig rapping but a rapper with a ghost writer? What the fuck happened? I swore I wouldn’t tell, but most of y’all sharing bars like you got the bottom bunk in a two man cell.”

Shots. Fired. You know who else noticed this? Drake. “Give these niggas the look, the verse, and even the hook. That’s why every song sound like Drake featuring Drake.”

Oh my.

In the second verse, “yams” takes on double meanings. You gotta be careful with that much power. Too much yams, slang for cocaine, was bad for Richard Pryor. Too much yams, slang for a woman’s vagina, was bad for Bill Clinton. In the final verse, Kendrick continues his funky walk down the street, draped in blackness. It opens with some patois, which is super-black. He’s repping Compton, which is also super-black. He’s feeling so good that he might run for mayor.

Kendrick, and Black America, surpassed what America said he would even live to see: “Made it past 25 and there I was a little nappy-headed nigga with the world behind him… Straight from the bottom, this the belly of the beast. From a peasant to a prince to a motherfuckin’ King.” No matter how hard America may try, Black America keeps advancing. From a peasant to a prince to the king. From slave to the spaceship, from property to president, we are resilient. We stay winning. King Kunta is a celebration of authentic, unapologetic blackness. No more revising our history, for better or worse. We advance.

King Kunta is a celebration of authentic, unapologetic blackness. No more revising our history, for better or worse. We advance.

Institutionalized

“Institutionalized” has Kendrick on display in full storytelling mode. After acknowledging the difficult position Black America is in, Kendrick admits that he isn’t fully fighting against it because he might be in too deep as well. The song opens with Kendrick rapping in a very vulnerable and honest tone as we hear his unfiltered thoughts that set up the story.

“What money got to do with it when I don’t know the full definition of a rap image? I’m trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it. Institutionalized, I keep running back for a visit. I said I’m trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it. Institutionalized. I could still kill me a nigga, so what?”

It doesn’t matter what his financial reality is, mentally he’s still trapped in the ghetto. And no matter how enlightened he sounds on these tracks where he’s highlighting and celebrating Black lives, culture, and influence, he could literally still “kill a nigga.” Being black in America is complex. While fighting against the system, we have to recognize how ingrained in us the system is.

Kendrick thinks about how amazing life is going to be when he’s achieved the American Dream. He’s paying his mom’s rent, freeing his homies from jail, getting high in the White House; he’s living! This all sounds nice, right? A little too nice, maybe. The verse comically continues with him saying other things that sound really nice on the track but don’t mean anything—“Zoom zoom zoom zoom zoom zoom”—and having birds chirping in the background like a Disney movie. Sometimes when we discuss Black America and our potential for future success, we get lost in pointless rhetoric. What we could do, where we could be, etc. etc. This daydream is then abruptly cut off by “shit” as we get back to reality.

“Life can be like a box of chocolate. Quid pro quo, something for something, that’s the obvious”

Kendrick explains that real life goes differently than you might expect it to go. Kendrick’s problem is that he’s too loyal to his homies. He tries to bring them everywhere with him and he pays for everything. But he realized what this was doing to them when he took a friend to the BET awards. “My niggas think I’m a god. Truthfully, all of them spoiled, usually you’re never charged/ But something came over you once I took you to the f*cking BET Awards.”

Kendrick was selling his friend a dream—the American Dream. He saw his usually calm friend get hype around all the wealth and get the desire for the American Dream in his eyes. “Somebody told me you thinking about snatching jewelry. I should’ve listened when my grandmama said to me: Shit don’t change till you get up and wash yo ass.” Kendrick shouldn’t have assumed that just showing his friends the riches of this new life would have been enough to change their mindsets. The only thing that will change their mindset is them getting up and changing for themselves. Much like Kendrick and his friend, black leaders (activists and rappers alike) have tried describing a promised land of black American success and yet the State of Black America continues to be bleak. It’s going to take a more concerted effort in the hearts and minds of all of us to change Black America, not just the outliers who managed to find success in the Swindle.

Snoop Dogg utilizes a cool Slick Rick’s “A Children Story”-style flow before the second verse to show that this verse is from Kendrick’s homie’s perspective. Kendrick’s homie responds to Kendrick’s embarrassment with the heartbreaking reality of his institutionalization.

“Fuck am I supposed to do when I’m looking at walking licks? The constant big money talk about the mansion and foreign whips… My defense mechanism tell me to get him quickly because he got it.”

Kendrick’s friend is rationally asking Kendrick how was he not supposed to notice all the flashy things these celebrities have while he’s at the BET Awards. He admits that he planned on robbing everyone in there. He saw it more as taking from the rich and giving to the poor, Robin Hood-style. “Institutionalized” is another example of how the American Dream is the American Swindle. Just like Kendrick’s friend, we live in a world where we are expected to display our success and opulence. We scroll Instagram for hours just looking at folks’ passive-aggressive attempts to prove that they are living the American Dream—cars, money, relationships, clothes, partying, etc. How are we not supposed to aspire to having such riches when that’s all we see all day? Institutionalization happens as quickly and as easily as signing up for any social media account.

These Walls

“These Walls” picks up the poem Kendrick weaves throughout several tracks:

“I remember you was conflicted. Misusing your influence. Sometimes I did the same.”

“These Walls” is about Kendrick misusing his rap celebrity influence to have sex with a woman whose man is in prison. It opens with a woman moaning so we know this is the “Poetic Justice” of the album. It’s a track for the ladies, right? Maybe not. The woman’s moaning sounds more painful than pleasurable. While my bias toward heralding Kendrick a genius is clear, this is one of the few issues I have with Kendrick. His proclivity for taking on the perspective of people unlike himself, women specifically, is admirable. However, when he takes on the perspective of a woman, he has a tendency to come from a place of pain, hurt, and turmoil. Either she’s a prostitute who might possibly have AIDS or she’s a woman who is so hurt by her man she “decides” to become a lesbian. It removes much of a woman’s agency and her ability to be a sexual being without conflict. Still, the perspective remains a real experience for many people at some point in their lives.

“If these walls could talk they’d tell me to swim good. No boat, I float better than he would… But your flood can be misunderstood. Wall telling me they full of paint, resentment. Need someone to live in them just to relieve tension. Me? I’m just a tenant. Landlord said these walls vacant more than a minute.”

Throughout most of the song, “these walls” represent the walls of a woman’s vagina. Kendrick details how much he loves having sex with this woman. Even though he knows she is only having sex with him because she misses her man, and even though it’s wrong, she just wants to enjoy it. Although initially their sex wasn’t perfect, now he knows exactly what to do to bring her pleasure. In the final verse we see “these walls” take on the meaning of a jail cell. Kendrick now addresses the woman’s significant other. He points out all the negative aspects of this man’s life:

“If your walls could talk, they’d tell you it’s too late. Your destiny accepted your fate… Wall telling you that commisary is low, race wars happening no calling C.O. No calling your mother to save you.”

Kendrick reveals the reason he’s treating this man so badly: this is the man who killed his friend Dave in the song “Sing About Me” from gkmc. So now Kendrick is misusing his influence to get revenge. But as the poem continues to tell us, “I remember you was conflicted misusing your influence. Sometimes I did the same. Abusing my power, full of resentment. Resentment that turned into a deep depression. Found myself screaming in a hotel room.” Turning to revenge and sex only resulted in depression. The next track “u” opens with Kendrick screaming.

“u”

This is easily the hardest track to write about. Kendrick Lamar did something amazing here. The stigma surrounding mental health in the black community is repulsive. We’re not supposed to express negative sentiments. We’re not supposed to show sadness or weakness. And particularly in the context of Kendrick’s black male narrative, hypermasculinity certainly doesn’t allow for the processing of feelings of depression. And yet, here on what will surely be one of the biggest rap albums of the year, if not the decade, we have an entire song about black depression.

I haven’t heard as accurate or realistic a portrayal of feelings of depression, angst, failure, fear, anxiety, and the like in a minute. If you’ve never experienced depression, first of all, huge congratulations. You are resilient and one of the lucky ones. If you want to take four minutes or so and really get into the mind of a depressed individual, this is the song. This is community service.

“u” opens with Kendrick literally just screaming. On an album essentially about embracing authentic blackness, there is an appropriate representation of black pain. James Baldwin once said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” And that’s what this is. Kendrick repeats “loving you is complicated” with real frustration and you feel as though while he’s looking in a mirror, he’s also talking to Black America.

“I place blame on you still. Place shame on you still. Feel like you ain’t shit. Feel like you don’t feel, confidence in yourself…”

“u” is an amazing exploration of individual and collective depression. Depression can be triggered by any number of things for individuals—poverty, a breakup, health issues, bad academic or professional performance, etc. But Black Americans are collectively vulnerable to it because of the State of Black America. Kendrick gives the main reason we could hate ourselves: seeing a problem in our community and not working hard enough to fix it or, even worse, not having noticed a problem at all.

“What can I blame you for? Nigga I can name several. Situation had stopped with your little sister baking, a baby inside just a teenager where’s your patience? Where was your antennas? Where was the influence you speak of? You preached in front of 100,000 but never reached her. I fucking tell you, you fucking failure: you ain’t no leader!”

Black America is infected by a host of ills—poverty, teen pregnancy, alcoholism, etc. Kendrick is angry at himself for having the celebrity influence of being able to talk to hundreds of thousands of people at a time but still not being able to reach someone close to him. At the same time, he’s talking to so-called black leaders. Kendrick has already established that the youth are going to lead the revolution, so he’s really talking to us. Here we are with social media letting us reach hundreds of thousands of people with one viral post and yet the State of Black America is dismal. We’re misusing our influence. This source of depression—failing our own people—is unique to Black Americans.

The show Broad City, on Comedy Central with Hannibal Buress, touches on this idea. Hannibal plays a dentist, Lincoln. When a woman jokes that he better do a good job on her friend’s teeth, he comments “If I mess up this white girl’s teeth, the black dentistry game is over, forever. I’m gonna get these teeth for my people”.

Black Americans don’t have the luxury of failing without consequence to others. Our failures reflect our entire people. When we fail, it leaves lasting scars. When we fail, we can get depressed. And it’s hard to look at the State of Black America right now and feel pride or success when unarmed black men and women are being killed and raped by those entrusted to uphold the law that keeps the American Dream together.

As an individual who everyday squares up against depression, I can attest that one trap of depression is the constant negative self-talk we fall into. “I never liked you! Forever despise you! I don’t need you! The world doesn’t need you! don’t let them deceive you!”

Housekeeping interrupts this track, as Kendrick is screaming in a hotel room, per his poem. “What do I got to do to get to you?” is sung almost drunkenly, which is how many people deal with depression—alcohol.

Kendrick talks about why he’s depressed. He speaks on the guilt he feels from being on tour while his friend was shot and died. He feels as though he failed him by not being there for him. He’s also not talking to some of his friends from back home and it’s making him drink more. As he’s drowning his sorrows in alcohol, he starts to think about killing himself.

“Shoulda killed your ass a long time ago. And if those mirrors could talk it would say you gotta go. And if I told your secrets, the world’ll know money can’t stop a suicidal weakness.”

Ultimately Kendrick’s (and our) quest for the American Dream ended with depression and a path toward self-extinction. We kill our own. We drown ourselves in alcohol. We rob our neighborhoods while supporting others. And this isn’t okay.

Alright

“Alright” opens with an allusion to The Color Purple, another classic black novel: “All my life I had to fight.” After the very heavy “u”, this is a perfectly placed, much needed track. “Alright” is a reassuring feel-good track. It’s also the beginning of the “looking forward” portion of the 2015 State of Black America. Kendrick can’t tell us how to improve until he tells us that our situation is fixable. Yes we’ve been through a lot. But we’re going to be okay. Writer and educator Melvin B. Tolson, on whose life the Oprah-produced Great Debaters film was based, wrote in Dark Symphony:

“Out of abysses of Illiteracy,

Through labyrinths of Lies,

Across waste lands of Disease…

We advance!

Out of dead-ends of Poverty,

Through wildernesses of

Superstition,

Across barricades of Jim Crowism

…We advance!

With the Peoples of the World…

We advance!”

The American Dream comes with terms and conditions. They said all men were free; Black Americans weren’t included in that statement. We’ve been barred from getting an education, lied to on multiple occasions (Ferguson, anyone?), given all kinds of sickness and disease, forced into a cycle of alcoholism and debt, and even still, Black America advances. We’re amazing.

“I’m fucked up. Homie you fucked up. But if God got us? Then we gon be alright!”

“Alright” also brings in the very important element of religion. Black Americans are notoriously and historically extremely deferential to religious authority. Yet even with this typical religious upbringing, self-identified Christians often live a seemingly contradictory lifestyle which is a picture that Kendrick paints extremely accurately.

“Painkillers only put me in the twilight. Where pretty pussy and Benjamin is the highlight. Now tell my mama I love her but this what I like! Lord knows!”

He lives a life of sin and he knows God knows it. He knows he can’t change it. Just as a fundamental part of Christianity is the unconditional love and forgiveness of God, Kendrick seems to be implying that Black America needs to forgive ourselves for being human.

“We been hurt, been down before. Nigga when our pride was low, looking at the world like, ‘Where do we go?’ Nigga and we hate po-po. Wanna kill us dead in the street for sure. Nigga, I’m at the preacher’s door. My knees getting weak and my gun might blow but we gon’ be alright.”

What kind of thesis on the State of Black America would be complete without highlighting what may be the greatest issue of our time: the killing of unarmed black men, women, and children by police officers?

Michael Brown was murdered by an officer while walking home, in front of multiple witnesses. That officer went free. Eric Garner was murdered on camera by a NYPD officer and that officer went free. Twelve-year-old Tamir Rice was playing in a park and was murdered by police officers on camera. 7-year-old Aiyana Jones was shot and killed by police officers. Her killer went free. Martese Johnson, a college student at the University of Virginia was beat until he was bloody and then shackled at the ankles because he allegedly used a fake ID. Turns out that was a lie.

Protests broke out in August in Ferguson after Michael Brown and in New York after the Eric Garner murder. Times are hard. Things seem dismal. But we gon’ be alright. Kendrick Lamar and Melvin B. Tolson both herald Black America’s ability to always be down for the cause and never down for the count. And even when it seems like we’ve hit rock bottom, we’re going to be alright. We’re going to advance.

Going with the religious imagery of “Alright”, Kendrick has a talk with the Devil. Lucifer, or Lucy, is repeating the same thing that “Uncle Sam” said in “Wesley’s Theory” “What you want you? A house or a car? 40 acres and a mule? A piano? A guitar? Anything! See my name is Lucy, I’m your dog!” Kendrick knows that the love of money and the American Dream is just the Devil tempting him but he can’t say no. So he takes the things and riches and gives it to his boys. This is where the album turns from historical context and present day situation to what our future could be like. “If I got it, then you know you got it. Heaven, I can reach you. Pet dog, pet dog, pet dog, my dog, that’s all.” Kendrick is going to use his ill-gotten gains for good. The “pet dog” phrase repeated three times likely refers to Cebereus, the three-headed dog that guards the gates of Hell. But he turned that beast into his bitch at the end—“My dog.” Kendrick is affirming that we don’t need to tear down the system. We might be able to succeed within it by overthrowing it.

“Alright” ends with more lines from the poem he’s been reciting.

“I remember you was conflicted. Misusing your influence. Sometimes I did the same. Abusing my power, full of resentment. Resentment that turned into a deep depression. Found myself screaming in the hotel room. I didn’t want self destruct. The evils of Lucy was all around me. So I went running for answers.”

For Sale?

Should we give in?

“What’s wrong, nigga? I thought you was keeping it gangsta! I thought this what you wanted! They say if you scared, go to church. But remember, he knows the bible too”

The Devil, Lucifer, is tempting Kendrick. He really wants him to fall into the trap. Kendrick remembers going to the mall and being tempted by all the material things for sale. Lucifer tries again to tempt Kendrick with the American Dream:

“Lucy gon fill your pockets. Lucy gon move your mama out of Compton. Inside the gigantic mansion like I promised. Lucy just want your trust and loyalty. Avoiding me? It’s not so easy I’m at these functions accordingly.”

The American Dream, now personified by Lucifer, is once again offering him everything he could want or need. And even if he doesn’t want it from the Devil, tough lucky avoiding it. The Devil tells him no matter how hard he tries to avoid him, no matter how hard he prays, Kendrick is going to end up signing the contract and selling his soul anyway. Because he still wants the American Dream.

The poem continues here “Found myself screaming in the hotel room. I didn’t wanna self destruct. The evils of Lucy was all around me. So I went running for answers. Until I came home”

Momma

“Momma” is about returning home, back to your roots, after a period of being lost and trying to find yourself. It’s about getting back to our people. To our blackness. “For Sale?” had Kendrick being tempted by the Devil. This is Kendrick getting back on track with God, or with his people. And he’s happy.

“This feeling is unmatched. This feeling is brought to you by adrenaline and good rap.”

When Kendrick released gkmc, people started to acknowledge his writing skills. He was on top of the world.

“Gambling Benjamin benefits, sinning in traffic. Spinning women in cartwheels, linen fabric on fashion. Winning in every decision. Kendrick is master that mastered it. Isn’t it lovely how menaces turned attraction?”

He got out the hood and achieved all this success. However, while most people would say Kendrick’s success is best marked by getting a plaque acknowledging that he sold many records, he views his greatest accomplishment as returning to his authentic blackness. Most of the lines in the second verse start with “I know.” He’s had the privilege of exploring the world and all it has to offer. He’s seen contradictions, he’s seen riches, he’s seen poverty.

“I know everything. I know Compton. I know street shit. I know shit that’s conscious. I know everything. I know lawyers, advertisement and sponsors. I know wisdom. I know bad religion. I know good karma. I know everything.”

And after all of his traveling the world and different experiences, he now knows what really matters. He knows what’s most important. “I know if I’m generous at heart, I don’t need recognition. The way I’m rewarded, well, that’s God’s decision.”

It’s clearer now what Kendrick, and Black America, need to do. Where, Kendrick returned to Compton to give back in whatever way he can in the first verse, the next verse recaps what happened when Kendrick went to Africa in 2013. He saw a kid that reminded him of himself. He looked just like him and likely had similar experiences such as being bad at home and hanging out in the street. This young Black kid acts as a voice of reason. He tells Kendrick he’s too Westernized. He’s internalized the American Dream to deleterious effects.

“Kendrick you do know my language. You just forgot because of what public schools had painted… Make a new list. Of everything you thought was progress and that was bullshit. I mean your life is full of turmoil, spoiled by fantasies… If you pick destiny over rest in peace, then be an advocate. Tell your homies especially to come back home.”

Our conceptualization of the American Dream has steered us wrong. And this little black boy is telling Kendrick that if he wants to uplift Black America, he has to get us to fall back in love with Us. The song then breaks here with “This is a world premiere” as though this is the new introduction to blackness. The final verse details our search for ourselves. For authenticity. For happiness.

“I been looking for you my whole life. An appetite for the feeling I can barely describe. Where you reside? Is it in a woman? Is it in money? Or mankind? Tell me something. Got me losing my mind! AH!”

Hood Politics

“I don’t give a f*ck about no politics in rap, my nigga”

Kendrick starts “Hood Politics” with a clear statement that this isn’t just about rap. “Hood Politics” highlights different situations with each verse. In the first, we get a brief history of why gangs formed—different cultures and values. People join gangs to be safe in their own ‘hoods and to be part of something greater. In the second verse, ‘hood politics refers to the government and shady politics. In the third verse, ‘hood politics refers to the rap game and fan consumption.

“They tell me it’s a new gang in town. From Compton to Congress, set tripping all around. Ain’t nothing new but a flu of new DemoCrips and ReBloodicans. Red state versus a blue state — which one you governing? They give us guns and drugs. Call us thugs.”

‘Hood politics aren’t unique to the ‘hoods of Compton and other low income areas often inhabited by black and Hispanic Americans. Kendrick points out that the same rules that institutionalized Kendrick’s ghetto mindset also govern America. While the two most arguably notorious gangs in America, the Bloods and the Crips, claim red and blue colors respectively, so do the two main political parties in America—Republicans and Democrats, respectively. Yet while people are quick to claim gang allegiance and activity is foolish and all over stupid colors, the government is essentially doing the same. It’s all the same. Members of the military and cops get guns and they’re freedom fighting heroes while black people get guns and they’re thugs.

“Critics want to mention that they miss when hip hop was rappin’. Motherfucker if you did, then Killer Mike would be platinum. Y’all priorities fucked up. Put energy in the wrong shit.

‘Hood politics in rap are equally as hypocritical. Fans claim they want “real hip hop” but won’t buy it when it gets made. Kendrick’s shoutout to Killer Mike, as well as the earlier implication that the government flooded the ‘hood with drugs, makes me think of Killer Mike’s song “Reagan.” Kendrick and Killer Mike have both made songs about Ronald Reagan’s administration and how the American government has truly swindled Black America with no remorse.

How Much a Dollar Cost

Again, Kendrick sits us down and tells a story. “How Much a Dollar Cost” is essentially a parable. He tell us a story about when he was in South Africa and was getting gas. The lesson is from Matthew 19:24, so now he’s citing the dopest black man ever, Jesus. Kendrick really drives home his hatred of capitalism and money with this song.

“And again I say unto you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” — Matthew 19:24

One day while still on his trip in South Africa, Kendrick is out driving his expensive car and stops to get gas. A homeless man asks him for some money but Kendrick assumes he’s going to spend the money on crack so he doesn’t give him any.

“A piece of crack that he wanted, I knew he was smoking. He begged and pleaded. Asked me to feed him. Twice. I didn’t believe it. Told him ‘Beat it’. Contributing money just for his pipe? I couldn’t see it.”

The homeless man replies that he actually isn’t addicted to anything and that he just wants one single bill. The chorus here, which features James Fauntleroy absolutely floating on the track, says a dollar is cheap. What’s worth more is feeding your mind. “Water. Sun. Love. The one you love. All you need, the air you breathe.” While Kendrick is sitting in his car, the homeless man is still staring at him and he asks Kendrick if he has ever read Exodus 14. Exodus 14 details the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt only to find themselves wandering around the desert. The Israelites were mad.

They said to Moses, “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you brought us to the desert to die? What have you done to us by bringing us out of Egypt? Didn’t we say to you in Egypt, ‘Leave us alone; let us serve the Egyptians’? It would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the desert!” -Exodus 14:11-12

Kendrick draws a parallel here between the struggle the Israelites faced and the struggle of Black Americans. Black Americans, as Kendrick’s thesis has continuously provided evidence for, have been through a lot. From slaves considered property, to citizens, to academics to doctors to lawyers to politicians to even having a black president, we’ve escaped slavery just like the Israelites. But still, even with all that progress, here we are with the 2015 State of Black America looking very, very bleak. Did we come this far just to die out by cops killing us? Or from killing ourselves? Spoiler alert: Moses came through and parted the Red Sea and the Israelites escaped. Also, all their enemies died when God closed the sea back up.

The homeless man tells Kendrick all of this. And Kendrick goes on a guilt trip. He’s mad a homeless man is pointing out that he’s living wrong. He tells him what the price of a dollar is: “I’ll tell you just how much a dollar cost: the price of having a spot in Heaven. Embrace your loss. I am God.”

Kendrick had a talk with God. And he learned that not only is money not going to bring happiness, it’s actually going to determine his fate, and it’s not a good outcome.

Complexion (A Zulu Love)

“Dark as the midnight hour or bright as the morning sun. Brown skinned, but your blue eyes tell me your mama can’t run.”

Kendrick shines a light on the tragic history that has lead to variations in our skin color. While skin color differences are used for jokes and even romantic preferences, Kendrick reminds us that there are phenotypically white traits we have that are likely because slave masters were raping our ancestors.

Kendrick then proclaims that we should let the Willie Lynch Theory reverse a million times. The Willie Lynch letter is my favorite piece of fake literature. The myth goes that this guy Willie Lynch was a brilliant racist genius and he predicted that after slavery, black people will still divide themselves by skin color and Instagram filters. Kendrick Lamar is a genius. But I want you all to know that Willie Lynch didn’t exist. He didn’t write a letter about how to control us. Someone else wrote it and trolled us. But I feel this track, regardless.

The Blacker the Berry

I appreciate this song much more in the context of the album. When it was first released, I rejected it. “The Blacker the Berry,” coupled with the statements Kendrick made about Ferguson, made me feel like Kendrick was blaming us for the current State of Black America. Kendrick Lamar commented on the killing of unarmed black teen Michael Brown in Ferguson by a police officer by saying,

“What happened should’ve never happened. Never. But when we don’t have respect for ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us? It starts from within. Don’t start with just a rally, don’t start from looting — it starts from within.”

“I’m the biggest hypocrite of 2015…”

And a lot of us collectively sighed. Not Kendrick. Not the Kendrick that was supposed to lead us into the promised land of dope hip hop and self love! Why was Kendrick using the distracting rhetoric of “Black people need to respect themselves before others will respect them?” As a fan, I was disappointed. As a black person, I was offended. As an activist, I was angered. With everything we’ve gone through, from enslavement to questionable medical practices to Jim Crow to today, with all these external forces aimed at us, why is Kendrick blaming the victim?

Kendrick aligns himself with us to tell us about his hypocrisy. He’s just like us. He knew this would be a hard pill to swallow so he makes this point very clear.

“I’m African-American. I’m African. I’m Black as the moon, heritage of small village. Pardon my residence. Came from the bottom of mankind. My hair is nappy. My dick is big. My nose is round and wide.”

After listening to “The Blacker the Berry” in the context of the album, I get it. I placed Kendrick in a box. We often create false dichotomies in Black America: Martin or Malcolm. Migos or Mos Def. You’re this or that. You can’t be both. You can’t like both. You can’t have both. So how dare he place even an ounce of culpability on Black America when we’ve ostensibly had everything thrown at us? But we can do both. We can rightfully place the blame on the American Swindle, but we have to own up to our part as well. I still fully and firmly believe that bringing up this myth of “black-on-black crime” is dangerously distracting rhetoric, as black-on-black crime and white-on-white crime occur at close to the same rate but I get what he’s saying in the context of the album.

America did this to us. America has fought us every step of the way. Every ounce of “freedom” we’ve gotten in this country was court-mandated because we fought for it. We died for it. And we have to hold ourselves to that same standard today as we did in the Civil Rights Era.

“So don’t matter how much I say I like to preach with the Panthers

Or tell Georgia State “Marcus Garvey got all the answers”

Or try to celebrate February like it’s my bday

Or eat watermelon, chicken, and Kool-Aid on weekdays

Or jump high enough to get Michael Jordan endorsements

Or watch BET cause urban support is important

So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street?

When gang banging made me kill a nigga blacker than me?

Hypocrite!”

You Ain’t Gotta Lie

“You Ain’t Gotta Lie” echoes the sentiment on “Real.” Comes back to confirm that you don’t need all the material things. You ain’t gotta lie. Kendrick is speaking to rappers who think they can’t sell by making good music. To black Americans who think they need to be a certain way to be deemed “authentic”. Just be black.

Asking, “where the hoes at?” to impress me. Asking, “where the moneybags?” to impress me. Say you got the burner stashed to impress me. It’s all in your head, homie. Asking “where the plug at?” to impress me. Asking “where the jug at?” to impress me You ain’t gotta lie to kick it my nigga. You ain’t gotta try so hard.

i

The album version of “i” (as opposed to the radio version) opens with a man shouting, “We’re bringing up nobody but the number one rapper in the world! He done travelled all over the world. He came back just to give you some game!”

This is an appropriate intro for the penultimate song on the album. This is the thesis conclusion. After the historical context the thesis took us through and the update on the State of Black America, here is Kendrick telling us the moral of the story. It’s us. It’s you. It’s me. i.

“I done been through a whole lot. Trial, tribulation, but I know God. The Devil wanna put me in a bowtie. Pray that the holy water don’t go dry.”

With this, we can’t help but think of the trials Kendrick has detailed. We learned about the American Dream’s insistence on loving money from “Wesley’s Theory.” We learned about how that can negatively affect us from “For Free?” We began to defiantly embrace our blackness on “King Kunta.” We recognized our limitations on “Institutionalized” and “These Walls.” We tried to stay in our comfort zone. We tried using other vices. This only brought us sorrow and depression on “u.” Kendrick reassured us that Black America is going to be okay, though, with “Alright.” On “For Sale?” we still battled our demons, but on “Momma,” we finally came home. We got back to our blackness. This wasn’t an easy process, though. Because we still live in America, and the politics of our situation our very real, “Hood Politics” taught us. “How Much A Dollar Cost” really hammered the point home that the American Dream’s conceptualization of “success” as “riches” is completely wrong. On “Complexion,” Kendrick reminds us that our blackness isn’t the same. We’re different. We have variations. But we still gotta love us. “The Blacker the Berry” showed us that while America really screwed us over and we’ve been through a lot, if we really love ourselves we have to take some personal responsibility and improve ourselves. “You Ain’t Gotta Lie” reminded us not to fall back into the traps of the American Dream. “i” has us at peak enlightenment.

“Not on my time! Not while I’m up here! We could save that shit for the streets. We could save that shit. This for the kids bro. 2015, niggas tired of playing victim, dog… How many niggas we done lost bro? This year alone? Exactly. So we ain’t got time to waste time my nigga… I say this because I love you niggas man.”

The album version of “i” has Kendrick making these guttural “huh!” sounds. Like he’s literally at war. His flow switches from this smooth jazzy flow to a beautiful but quick-paced rhythm like an expert boxer. On this version of “i,” Kendrick is appealing to his people. He’s trying to rally people. He’s trying to keep the peace. A fight breaks out on the album version, as well, and he tries to get us back together. Kendrick steps into his role as a leader of Black America.

As we work to love us, our history, our culture, our people, and also try to move forward, we’re not going to all agree on the method. We all want freedom, but we have different ways of getting there. Regardless of our path, we have a unity based in love. Kendrick goes on to speak to the people in the crowd, you and me, and the rest of Black America. He’s rapping a capella so it truly feels like a revolutionary speech. This is his rallying cry.

“I promised Dave I’d never use the phrase ‘fuck nigga’

He said, ‘Think about what you saying. ‘Fuck niggas’.

No better than Samuel on D’jango. No better than a white man with slave boats.

So ima dedicate this one verse to Oprah

On how the infamous, sensitive N-word control us.

So many artists gave her an explanation to hold us.

Well this is my explanation straight from Ethiopia.

N-E-G-U-S

Definition: royalty, king royalty. Wait, listen.

N-E-G-U-S

Description: Black emperor, King, ruler. Now let me finish.

The history books overlooked the word and hide it.

America tried to make it to a house divided

The homies don’t recognize we be using it wrong.

So Ima break it down and put my game in the song

N-E-G-U-S, say it with me.

Or say no more. Black stars can come and get me.

Take it from Oprah Winfrey.

Tell her she right on time.

Kendrick Lamar, by far, the realest Negus alive.”

Mortal Man

“As I lead this army make room for mistakes and depression. And with that being said, my nigga, let me ask this question: When shit hit the fan, is you still a fan?”

The last song on the album, “Mortal Man” has Kendrick asking us to keep this all in perspective. Kendrick is still human. Much like Mandela, and all the other great black heroes Kendrick draws on for this album, from Moses to Malcolm, he’s only a human. “If I’m tried in a court of law, if the industry cut me off. If the government want me dead, plant cocaine in my car. Would you judge me a drug kid or see me as K. Lamar?”

Kendrick noted on “Hiiipower,”

And I want everybody to view my autopsy. So you can see exactly where the government had shot me. No conspiracy, my fate is inevitable. They play musical chairs once I’m on that pedestal.”

There is a stark consequence to preaching these truths and rallying Black America toward self love. Many of the great black people Kendrick called on in this album suffered a tragic death or were murdered. This entire album features a poem that is read to Tupac Shakur on this track, whose life was also cut short. Kendrick wants to know that if he can’t keep leading us, are we still going to appreciate what he has done.

“How many leaders you said you needed then left them for dead? Is it Moses? Is it Huey Newton or Detroit Red? I sit Martin Luther, JFK, shoot or you assassin. Is it Jackie, is it Jesse, oh I know it’s Michael Jackson. When shit hit the fan is you still a fan? That nigga gave us Billie Jean, you say he touched those kids?”

Black America, if we’re going to move forward, we have to treat those who have the courage to stand up and lead with more loyalty. One of my favorite pieces I’ve ever read is by musician Phonte of Little Brother and the Foreign Exchange titled, “My Hero Ain’t Molest Them Bitch Ass Kids.” With a title like that, you already know you’re in for a treat. Essentially, Phonte highlights the ridiculousness of the accusations against Michael Jackson. It ends with:

I am not attempting to paint Michael Jackson as a saint, as no man ever lives up to such a lofty title. But to me, the phrase ‘no good deed goes unpunished’ seems to sum up Michael Jackson’s life more than ever. Why would people try to tear down a man who constantly used his power, money, and influence to help others? Why would people express such disgust and contempt for a man who constantly sang of love and peace and used his talent to entertain, uplift, and inspire millions? Tell them that it’s human nature, I suppose…Rest in Peace, Brother Michael.”

“When shit hit the fan, is you still a fan” is about more than just being a fan of Kendrick or any other artist, however. It’s about being down for the cause. When the fight gets real, are you still going to maintain your commitment? Paul Mooney once said, “Everybody wanna be a nigga, but don’t nobody wanna be a nigga.” When it’s not glossy and pretty, are you still a fan of black culture and, more importantly, black people?

The track and the album ends with Kendrick reciting his poem in full to Tupac.

I remember you was conflicted. Misusing your influence. Sometimes I did the same. Abusing my power, full of resentment, resentment that turned into a deep depression. Found myself screaming in the hotel room. I didn’t wanna self destruct. The evils of Lucy was all around me so I went running for answers until I came home. But that didn’t stop survivor’s guilt. Going back and forth trying to convince myself the stripes I earned or maybe how A-1 my foundation was. But while my loved ones was fighting the continuous war back in the city, I was entering a new one: a war that was based on Apartheid and discrimination. Made me wanna go back to the city and tell the homies what I learned. The word was respect. Just because you were a different gang color than mine doesn’t mean I can’t respect you as a black man. Forgetting all the pain and hurt we caused each other in these streets. If I respect you, we unify and stop the enemy from killing us. but I don’t know. I’m no mortal man. Maybe I’m just another nigga.”

Tupac tells Kendrick, “The poor people is gonna open up this whole world and swallow up the rich people. Cause the rich people gonna be so fat, they gonna be so appetizing… The poor gonna be so poor and hungry, there might be some cannibalism out this mutha, they might eat the rich.”

Kendrick asks Pac, “What you think is the future for me and my generation today?” and Pac replies, “I think niggas is tired of grabbing shit out the stores and next time it’s a riot, there’s gonna be bloodshed for real. I don’t think America know that. I think America think we was just playing and it’s gonna be some more playing. But it ain’t gonna be no playing. It’s gonna be murder. It’s gonna be like Nat Turner, 1831 up in this motherfucker. You know what I’m saying? It’s gonna happen.”

Kendrick goes on to explain the butterfly metaphor: “The caterpillar is a prisoner to the streets that conceived it. It’s only job is to eat or consume everything around it, in order to protect itself from this mad city. The butterfly represents the talent, the thoughtfulness, and the beauty within the caterpillar.”

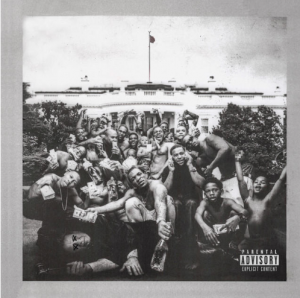

I know. This was a lot. This is my interpretation of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly. I believe he laid out a thesis. I hope after reading this you’re only more interested in hearing the album again, and again, and again. After all this analysis and critique, I didn’t even touch on the samples used here, and trust they are equally as black. From jazz to funk to hip hop, there is a story being told there as well. Future research into the album should also explore the poem and conversation with Tupac in more depth. And that album cover? Oh man. There is so much to the picture being painted by Kendrick Lamar. I don’t know it all. But I hope it sparks discussion and marks a return to truly embracing our blackness.