He only remembers any of the situation because of its strict deviation from patterns observed. He’s forgotten most of the details of how it made him feel. But it obviously impacted him, to where this memory runs in a loop in the depths of his mind’s archives, ever-on-guard for a situation necessitating it’s recollection.

In the past when summoned to the principal’s office, it was to be lectured on topics like disobedience and consideration, why he shouldn’t pull his pants down in class and those sort of themes. Not for lack of understanding, but because of sheer and utter disinterest, it would all go in one ear and out of the other. He was about 6-years old. His attention was laser focused on the knowledge that these sorts of days were always followed by a call to his mother, who arrived to school late afternoon in livid-mode, guns a-blazing both at Joe and at his teachers — all of whom needed to let her work in peace. His mother never understood the logic behind calling a parent while at work to speak on misbehavior, and spared not an inkling of verbosity telling him so, ensuring that his journey would be a rather uneventful trip as his mother reserved her energy for the ass whooping to come not long after their arrival home. He’d count the bumps in the road as they pushed forward, imagining one of them could stop the car. That never happened.

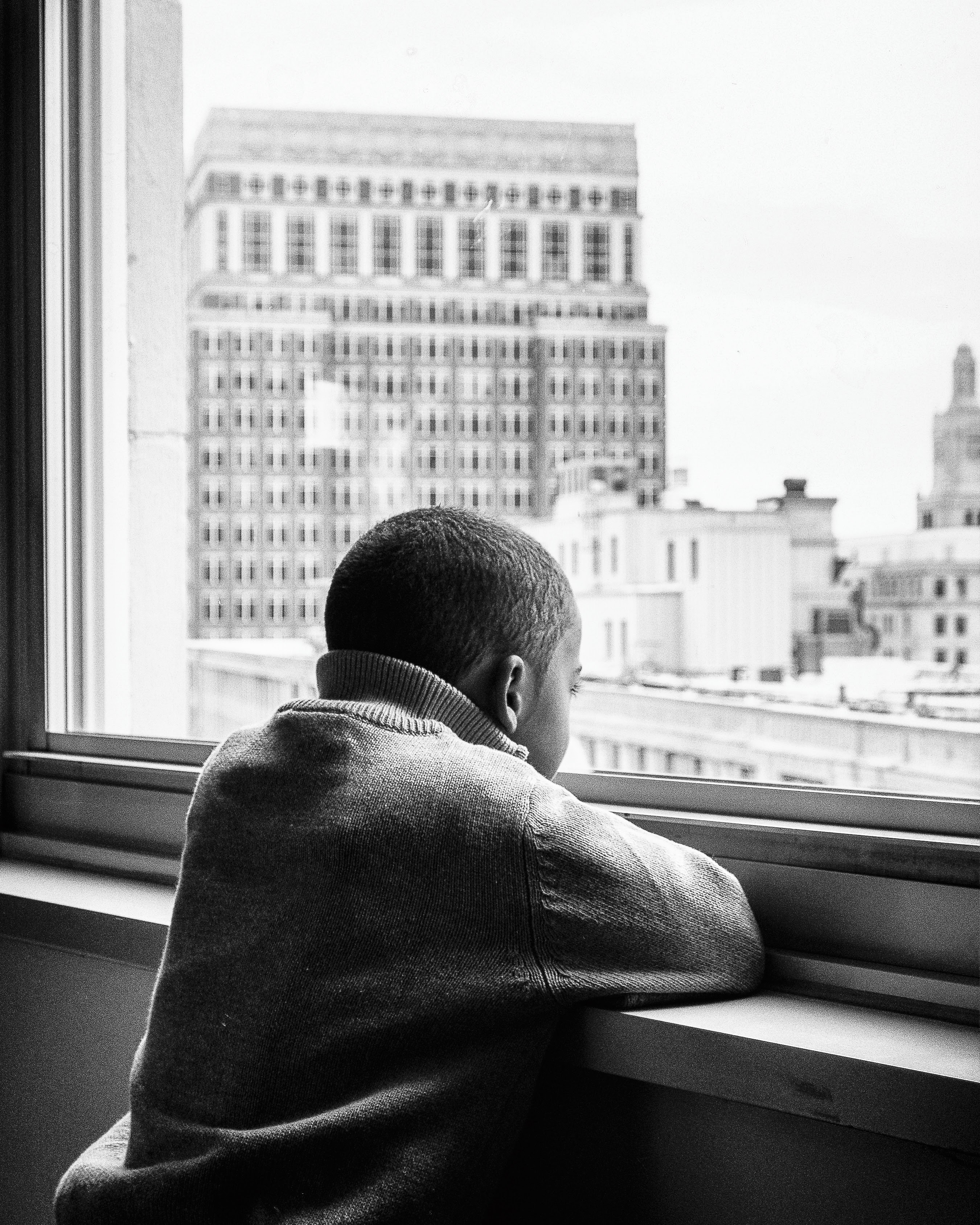

This time was different, though. As the class snickered, attempting to instigate a battle with fear of an impending doom, he sat resolute in confidence that he’d done nothing wrong. They must have been confused. It had been weeks since the last time he’d done the thing they called misbehaving. He took his time and hop-scotched the alternating tiles down the halls of the school, allowing the metallic lockers along the way to audibly greet his knuckles, making his presence known to the world — in case of the worst scenario. If he actually was in trouble for some past overlooked transgression, all bets were off. Rather confused, he walked through the noise, then the hall, then the door of the principal’s office, only to be told he was being checked out of school early — by a man he’d not seen in some weeks. His father.

The walk to the car was a pride-filled one. Even though he had his feelings towards his father, the man existed. He’d crafted many lies as to the causes of the man’s absence, so when his classmates saw his father in person, they gave him Superman-like admiration — which Shane graciously received, playing the part with a youthful zest as he lead Joe to an unfamiliar car. The man seemed to be doing well for himself.

Shane’s absence had done a number on the boy. He found himself unable to feel excitement at the prospect of spending time alone with the man. His father made him feel like salt on a snail, and confused him.

He didn’t know which he was, the slime soaked sodium or the remnants of a being made mostly of water. Sometimes you just feel like someone doesn’t like you. His father looked at him like one of those people. But there was still a love, a nostalgia they both saw it as. This seemed to be a meeting to repair the damage done, but all the boy could see was a mission.

Continued in Crossroads: Part Two.