The concept of “Afro-Cuban” art has always garnered a great deal of attention from enthusiasts of the African Diaspora. Although it is ubiquitous and synonymous with most Cuban art on the island, drawing no particular distinction, this hyphenated genre among a more global audience is defined more by the subject of Black culture in Cuba and not necessarily the African origin of the Cuban artists themselves. The culture is expressed in obvious subjects such as the unique sounds of the Conga drums and images of Orishas (the Yoruba deities portrayed by Catholic saints and depictions of the Virgin Mary) to the subtler, albeit famous Arroz con Pollo.

In spite of this, the way Afro-Cuban art has portrayed the people of African descent in film in particular has historically been through the lens of the ruling class of European descent. As the product of a colonial society, Blacks of Cuban heritage have been and are too often portrayed as stereotypes and caricatures, unable to truly self-express as protagonists with rich and complete functions, even in their own narratives. However, filmmaker Sergio Giral has played a tremendous role in bucking this trend.

For over fifty years, Giral has amassed a lifetime’s body of work, writing and bringing to the big screen the history of the African Diaspora in Cuba from an Afro-centric perspective. Fresh from a presentation of his newest project at Art of Black Miami, Giral spoke with me about how he continues to give voice to the Afro-Cuban community through his unique and thought-provoking films, adding pigment to an otherwise invisible color.

Pablo Velez: You were born in Havana in 1937 and lived there until moving to the United States at 8 years old. As a young man, you were an aspiring painter in New York City. However, after the Castro Revolution when many Cubans were leaving the island, you actually returned. Why?

Sergio Giral: My mother was African-American from Brooklyn, and my father, a White Cuban from Havana. Toward the end of World War II, we moved to New York City as my father was presented with a business opportunity. I grew up in Greenwich Village during the height of the Beatnik generation. Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac were my idols, and Jean-Paul Sartre, my guru.

I was in my early 20s, painting and waiting tables at The Play House on MacDougal Street. I became friends with a fellow waiter named Néstor Almendros. At the time, he was a young filmmaker of Catalan origin who had lived in Cuba because his family was exiled by the Franco regime. Almendros, who would become an award-winning cinematographer (winning the Oscar for best cinematography in 1979 for Days of Heaven, and later nominated for Sophie’s Choice, Kramer v. Kramer, and The Blue Lagoon) was very much taken by ideals of the Cuban revolution, and ended up back on the island.

While working for the ICAIC (The Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry) as a director of photography, Néstor invited me to join him and the other filmmakers of the Cuban cinema.

The temptation was great. At the time, the revolution had these romantic and irresistible characteristics of social justice and I wanted to be a part of that movement. I decided to move to Cuba in 1961 where I started to learn the business from scratch, being that I did not have any prior formal training.

Pablo: When did you become interested in the Afro-Cuban narrative and what about it was so compelling that caused you to make it the focus of your life’s work?

Sergio: When I arrived in Cuba, one of the aspects that caught my attention was the popular culture and historicity of Black Cubans. I researched the work of relevant ethnologists such as Moreno Fraginal, Jose Luciano Franco, and Perez de la Riva.

The subject completely fascinated me. From the powerful, ubiquitous sound of the drums in Cuban music to the mysticism of the Yoruba religion, I found the African contribution to the culture to be essential and worth emphasizing. It was then that I decided that film could give me the opportunity to develop and bring to light the role of Blacks in Cuban history and also draw attention to issues of contemporary racism as a by-product of the African slave trade in the New World.

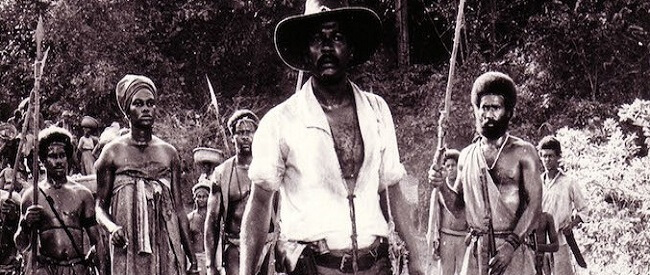

Pablo: You are most known for your “Colonial Trilogy,” which includes the award-winning films El Otro Francisco (The Other Francisco, 1975), Rancheador (Slave Hunter, 1979), and Maluala (1979). What inspired you to make these films?

Sergio: In my films, I’ve always focused the camera’s point of view to the background, where slaves, maids, and working class Black characters traditionally existed. This is exposed in “The Other Francisco,” a twist on the impossible love story between two Black slaves, “Slave Hunter,” and “Maluala,” all of which display the ordeals of Black Cubans in search of freedom and equality in 19th Century Cuba. The main reason why I made those films was my need to express the role of Black Cubans in history.

The Other Francisco is based on the first abolitionist novel in the Americas, “Francisco”, by Anselmo Suárez, which was written over a decade before the US publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. My film reveals the realities of slavery in a parallel docudrama format in contrast to the romantic depiction in the novel.

Maluala is a tale of run-away slaves known as “cimarrones” (maroons) who overpowered their Spanish masters, fleeing and settling in secret settlements (palenques) in the mountains of eastern Cuba and the Spanish colonial government’s efforts to use trickery and force in order to destroy their community.

Rancheador (Slave Hunter) is based on the true story of Francisco Estevez, a bloodthirsty slave hunter and his obsessive pursuit of Madre Melchora, a legendary maroon (run-away slave) who was also a symbol of freedom.

Pablo: Your films, Techo de Vidrio (The Glass Ceiling, 1982) and Maria Antonia (1990), were a departure from the colonial narrative and dealt with contemporary cultural issues. What were the messages you were delivering through these works?

Sergio: In these films, I wanted to emphasize the continuing racial divide that continued to exist in Cuba. The Revolution, which purported to end racism, ended up merely masking it in a different form.

The Glass Ceiling is a story about the racial inequities that occur in the contemporary Cuban workplace. The protagonist is a black Cuban construction manager, who is under investigation for taking some of the excess concrete and giving it to a poor worker to make necessary repairs to his home. The white Cuban Architect/Engineer on the project also steals materials, but to make cosmetic upgrades on his home. The latter is not held accountable in the least. It is a snapshot of the hypocrisy of a system that claims to provide equal opportunities and access to the state’s resources.

Maria Antonia (is actually an adaptation of a 1967 theatrical play by the same name (written by Eugenio Hernandez Espinosa). The play is the Afro-Cuban adaptation of “Carmen,” the famous opera by Georges Bizet (1875). The protagonist is a stereotypical “mulata” woman, symbolic of the general social issues endured by bi-racial women in Cuba. She is a frustrated temptress, desired by men of all races, but respected by none. A second-class citizen in constant conflict with her environment, she struggles to cope with her identity while attempting to maintain her passionate, yet abusive relationship with a young Black boxer destined to leave her for fame and glory in the United States.

Pablo: Returning to the United States was a decision you acted upon in 1991. What spurred your departure from Cuba?

Sergio: When I decided to go to the US, I was actually at the peak of my career in Cuba. However, the hypocrisy of the system became too overwhelming. The romantic ideals that had brought me to the island as a young man had slowly evaporated over time. I found the country’s double standards perpetuated the racism, social inequality, and political repression that it pretended to cure.

The socialist system itself bankrupted not only our pockets, but also our intellectual and artistic expression. Many scripts were rewritten and films were re-edited or simply banned or confiscated. As a result of these curbs, three generations of filmmakers abandoned the country seeking freedom of speech abroad. Almendros, who originally brought me to the island, was among this group that left.

Then there was just the outright corruption. The government had executed several leaders accused of “treason” and other alleged crimes. No one was immune when the government was in search of a scapegoat. Although my films had official acceptance and I was never under any direct threat, these conditions were the last straw for my stay under the regime.

Pablo: Finding yourself in Miami, you continued your activism in bringing about films with social messages in the US, such as “Chronicle of An Ordinance (2000)” and “Dos Veces Ana (Two Times Ana)” in 2010. Currently, you are in the middle of production for The Invisible Color. What is the main focus of this documentary?

Sergio: This documentary investigates Black Cuban exile in South Florida, from the first wave of political refugees in the aftermath of the 1959 revolution to the present. It tracks their presence throughout the region, and highlights their contributions to Miami’s civic culture through testimonial and visual documentation.

While any visitor to Cuba will notice the presence of Afro-descendants everywhere, Black Cubans are practically invisible in the biggest Cuban enclave outside of the island: Miami-Dade County. The Miami exile is predominantly white. The Invisible Color seeks to both address and redress this silence by showcasing Afro-Cubans’ experiences in Miami as both exiles and immigrants. My film focuses on their relations with their white co-nationals and other groups in the city at large, as well as their contributions in contemporary American society. In doing so, the documentary critically assesses the identity of Black Cubans in American history and popular culture.