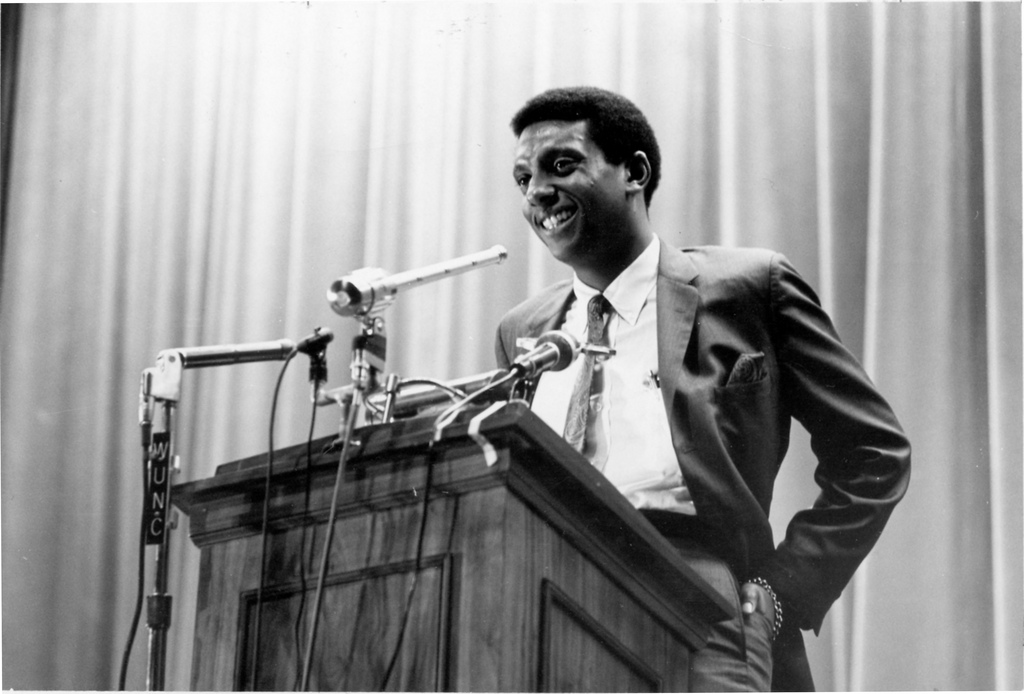

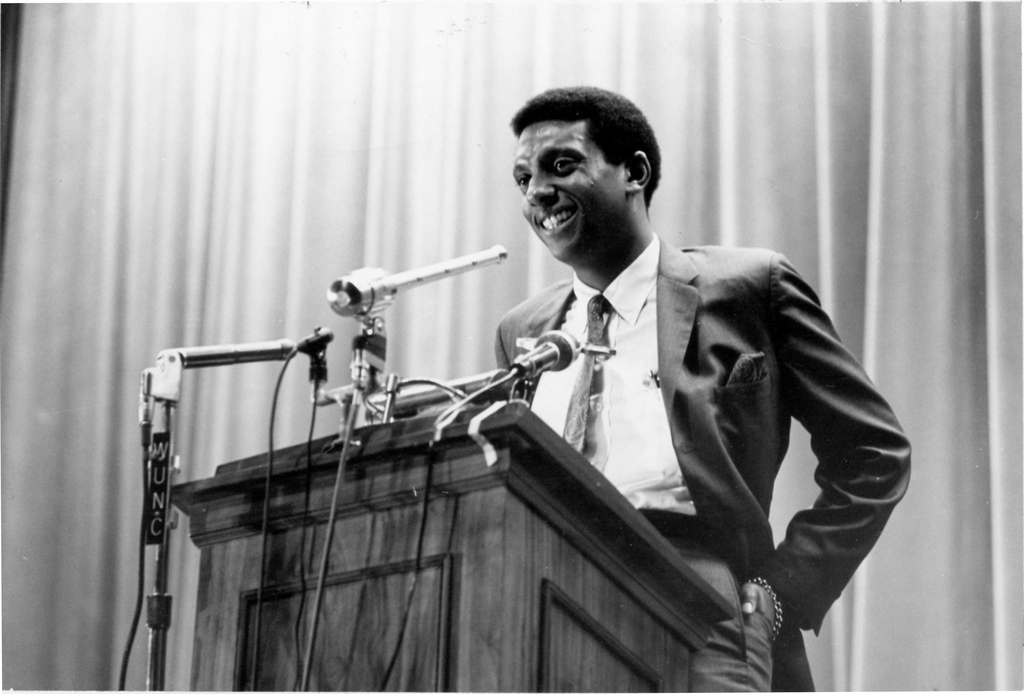

Cocky. Self-assured. Reckless. Radical. Activist. Organizer. Leader.

By the summer of 1966, any of these words would be used to describe the man who coined the term Black Power, signaling the official shift from the Civil Rights Movement to the Black Power Movement. No man made a greater contribution to the Civil Rights Movement while receiving lesser credit. And yet, until recently, his contributions have all but been written out of mainstream history books.

Stokely Carmichael was born in Trinidad on June 29, 1941. In 1952, Stokely’s family left Trinidad and landed in New York City. Stokely would join Marcus Garvey and DJ Kool Herc (both from Jamaica) as Afro-Caribbean immigrants and innovators who would make a powerful impact on black culture in America.

Stokely Carmichael cut his teeth on civil rights activism while a philosophy major at Howard University. While a student in D.C., Stokely became deeply involved in the burgeoning movement. He was mentored by the legendary Ella Baker, who had helped form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Shaw University over Easter weekend, April 16, 1961.

During the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the youth-led SNCC would employ everything from sit-ins to Freedom Rides, from organizing sharecroppers to coordinating voter mobilization drives, all in an attempt to cut down the monster of Jim Crow segregation in the South. Stokely participated in all of these actions, learning the ropes of grassroots civil rights organizing. He would later become famous for coining a famous phrase “Black Power,” which would become a lightning rod for controversy.

But Stokely was both experienced and deeply steeped in the nuts and bolts of movement organizing in the stronghold of the terrorist group known as the Ku Klux Klan, the Deep South. These were the days when the Klan and groups such as the White Citizens’ Council targeted and killed movement leaders such as Medgar Evers in June 1963. He, along with many other bold SNCC freedom fighters, had helped organize the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LFCO) in Alabama. The LFCO registered thousands of black voters and mobilized sharecroppers and domestic maids into a potent voting bloc that gave them real political power for the first time in their lives, and black political representation for the first time since Reconstruction.

No man made a greater contribution to the Civil Rights Movement while receiving lesser credit.

As Stokely recalls in his autobiography Ready for the Revolution, SNCC activists both helped organize sharecroppers in the Deep South and learned from them as well. He was in Mississippi when the white supremacist terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan killed civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman in June 1964. Stokely was in the South when the same terrorist group bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four girls—Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Carol Denise McNair (age 11), Carole Robertson (age 14), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14). After the death of so many activists and members of the community at the hands of the killer Klan, a group of men began organizing in 1964 for armed resistance to racist terrorism. The group called themselves the Deacons for Defense and Justice, and they worked along side SNCC and other civil rights groups to provide armed protection from the attacks waged by the Klan in Mississippi and Louisiana (which were often supported by state and local officials).

Armed resistance to real-life terror or self-defense against white supremacist terrorism was the response of black people who had lived daily under a stark Jim Crow regime. It was in this fiery cauldron of rising self-determination and self-defense that Stokely issued the call for Black Power in 1966, after he was elected chairman of SNCC. James Meredith, original leader of the March Against Fear, held that year, had been brutally attacked almost to the point of death.

As Stokely recalled in his autobiography, a summit was held in Memphis to decide whether or not the march would reboot to continue and if so how. Five civil rights organizations were represented at the meeting: the NAACP, the Urban League, Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and SNCC. Stokely and his colleagues were selected to represent SNCC at the summit. The dealbreaker for the organizations was whether or not the Deacons for Defense would be alongside the marchers to provide protection, as they had at many other marches and functions in the South since early 1965. Stokely argued passionately for armed resistance, positing that it would be foolish to send marchers—white or black—into harm’s way and in the hands of a ruthless enemy, without the well-trained, well-disciplined, armed members of the Deacons for Defense. Stokely and Floyd McKissick (the leader of CORE) both supported the presence of the Deacons.

On the other side, Roy Wilkens of the NAACP and Whitney Young of the Urban League argued against the participation of the Deacons. Dr. Martin Luther King, who had served as the moderator for the entire meeting, was the fifth and deciding vote. Dr. King cast his vote in favor of allowing the Deacons to participate in the March Against Fear. SNCC had formed deep connections in Delta communities along the I-55 route the march would take along the way to the capital of Mississippi, Jackson. It was their organizing prowess and “boots on the ground” that turned out people to participate in the march and encouraged sharecroppers working the cotton fields to march literally against fear.

Armed resistance to real-life terror or self-defense against white supremacist terrorism was the response of black people who had lived daily under a stark Jim Crow regime. It was in this fiery cauldron of rising self-determination and self-defense that Stokely issued the call for Black Power.

It was fear that kept black folks in line. Fear that the Klan instilled with every brutal and violent act. Fear was the toxic element borne of 3,959 lynchings of black people in twelve Southern states between 1877 and 1950. Fear was the ingredient perpetrated by nearly a hundred massive acts of collective punishments exacted against black communities via mob violence, riots, coup d’tats, and pogroms. The antidote, surmised Stokely on the road to Jackson, was Black Power. Power to stand up and stop Klan aggression. Power to break the back of Jim Crow. Power to repel the killers of Evers, the four little girls in Birmingham, Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman.

As Stokely would define the phrase at a speech in 1967: “Black Power is the coming together of black people to fight for their liberation by any means necessary.” For Stokely, Black Power did not mean white people were absent from the movement to end racism. In his speech at the University of California at Berkeley in 1966, Stokely advocated for dual movements: one inside black communities, where black people would work to address the damage of racism, and one inside of white communities, where white allies would teach other whites to become anti-racists.

SNCC members would later write position papers and Stokely would later write books to further elaborate the phrase. But in raising the phrase Black Power, Stokely went to the heart of the matter in 1966. Yes, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 brought about the end of the most visible forms of Jim Crow in public facilities and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 legally eliminated barriers to voting, but the Klan and other government officials were not swayed. These “rights” still had to be enforced and implemented in the face of stiff resistance. Further, in 1966 during the March Against Fear, black people still could not live where they wanted due to continued housing and neighborhood residential segregation. It wasn’t until the assassination of Dr. King in 1968 that Congress finally decided to pass the Fair Housing Act. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 contained language that the federal government would “affirmatively further” fair housing, an action that has only now in 2015 been implemented by the Federal government as a rule in the Obama administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Black Power, as Stokely articulated it, was not only the antidote to fear imposed by Klan terrorism, but the ability to neutralize the right-wing and racist attacks on black lives. In the age of #BlackLivesMatter, we are still combating many of the same scourges that plagued our ancestors: segregated neighborhoods that are now hypersegregated, resegregating schools and school districts, convict leasing that has morphed into mass incarceration, attacks on black churches, and the ever-present police brutality and killing of unarmed black people. We are also facing new threats: the War on Drugs, gentrification, the dismantling of public housing, mass foreclosures, and mass school closures.

Stokely advocated for dual movements: one inside black communities, where black people would work to address the damage of racism, and one inside of white communities, where white allies would teach other whites to become anti-racists.

The need for Black Power has not diminished, even with the election of the first president of African descent in America. Until segregation is ended in this country without the deployment of forced displacement, until white cops stop killing unarmed black women, children, and men, until we dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline, people of African descent must “fight for our liberation by any means necessary.”

Stokely’s life and legacy of movement-building among the dispossessed, supporting indigenous leadership, consensus decision-making, and local innovations to solve context-specific problems are a part and parcel of the long-neglected core principles of SNCC (and Ella Baker). Black Power, ultimately, is not a grand articulation forged in academic pontification, but a rooted and grounded vision for empowerment that arose out of the philosophy of Ella Baker, gestated in the womb of SNCC, matured in organizations such as the Lowndes County Freedom Organization and Deacons for Defense, and was given birth by Stokely Carmichael on the road to Jackson during the fearless March Against Fear.