The part of Florida I’m from is remarkably more like Mobile than Miami. From Grandma’s house, it’s a short drive to the Alabama border, the gateway to the Heart of Dixie. Riding in the backseat as kid, with Mom driving, I was always amused by the fact that, as we crossed that border, at some point Mom would be in one state and I in the other.

We crossed the border often. There was no mall in my hometown, so we’d travel to Dothan, Alabama, to shop for birthday gifts or Christmas gifts or just to get out of the house. The trip along state route 53 took us through a small Alabama town, Cottonwood, where there’s but one traffic light. Whites live on one side of town. Blacks live on the other, along Granger Street, near Whitehead Milling Co., a feed dealer and the town’s sole industry.

Something that will always stay with me is a time we passed through Cottonwood and I saw, in the unkempt front yard of a shabby trailer, a big, weathered rebel flag and a sign advertising a Ku Klux Klan rally.

The sight shook me. I was 13, and I’d seen that flag before, around my hometown; I knew it wasn’t exactly a welcome mat for folks like me. But I’d only ever seen traces of the KKK in movies. Because so many of my family and family friends often passed through that town,“Don’t speed through Cottonwood” became the sage advice among us.

The effect that moment had on me back then was terror. The caution required for us to drive through that town was terror’s result. Make no mistake, those who pledge allegiance to the Confederate flag are terrorists.

Make no mistake, those who pledge allegiance to the Confederate flag are terrorists.

On June 17, 2015, in an act of terror, evil walked into Emanuel A.M.E Church. A killer, drunk with hate, wreaked terror in a sanctuary, taking the lives of nine worshippers who, by his own account, were almost too nice to kill. The victims were, as President Obama put it, each in different phases of life.

A young state senator-turned-pastor, kind and thoughtful by all accounts, who gave voice to the voiceless.

Devoted wives and mothers, husbands and fathers.

A young man, who had recently graduated college, trying to find his way in life.

Elders too fragile to mount any real defense.

That the Confederate flag—the very symbol of that killer’s mens rea—stood on South Carolina Capitol grounds, flapping in the winds and endorsing hate as Senator Pinckney’s coffin passed to lie in state, shocks the conscience. Inside the building’s rotunda, a paltry black curtain placed at a window attempted but failed to prevent that same flag from being the backdrop to Mr. Pinckney’s open casket. On a day that was supposed to be about respect, that flag gave insult.

A raised flag bears unique significance. The American flag, of course, has borne out that significance at our most critical times in history—at Iwo Jima, on the Moon, out of the World Trade Center rubble. It’s a territorial claim, a symbol of pride, a show of resolve.

Confederate flag-wavers understand this significance—it’s why they want the rebel flag to fly. It fulfills their antebellum fantasies, their hankering for strange fruit.

They claim it represents pride in their region, heritage, and ancestors when they have no region, when hate is their heritage, and when their great-great-grandfathers were on the wrong side of history.

To contend that the rebel flag may be anything other than a symbol that divides us is pure imagination. To assert that it may be celebrated without also celebrating hate is being untethered to reality. To fly it on the capitol grounds in South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi or elsewhere is a slight to America’s unity.

It must come down. It must stay down.

Last week was a defining moment for Mr. Obama’s presidency. His political victories were significant and consequential. His candor on race was even more so.

The notion of our first black president eulogizing a black state senator assassinated in a hate crime straight out of the 1960s made for a poignant contrast. It reminded us, at once, that we cannot deny progress, but also that we aren’t there yet.

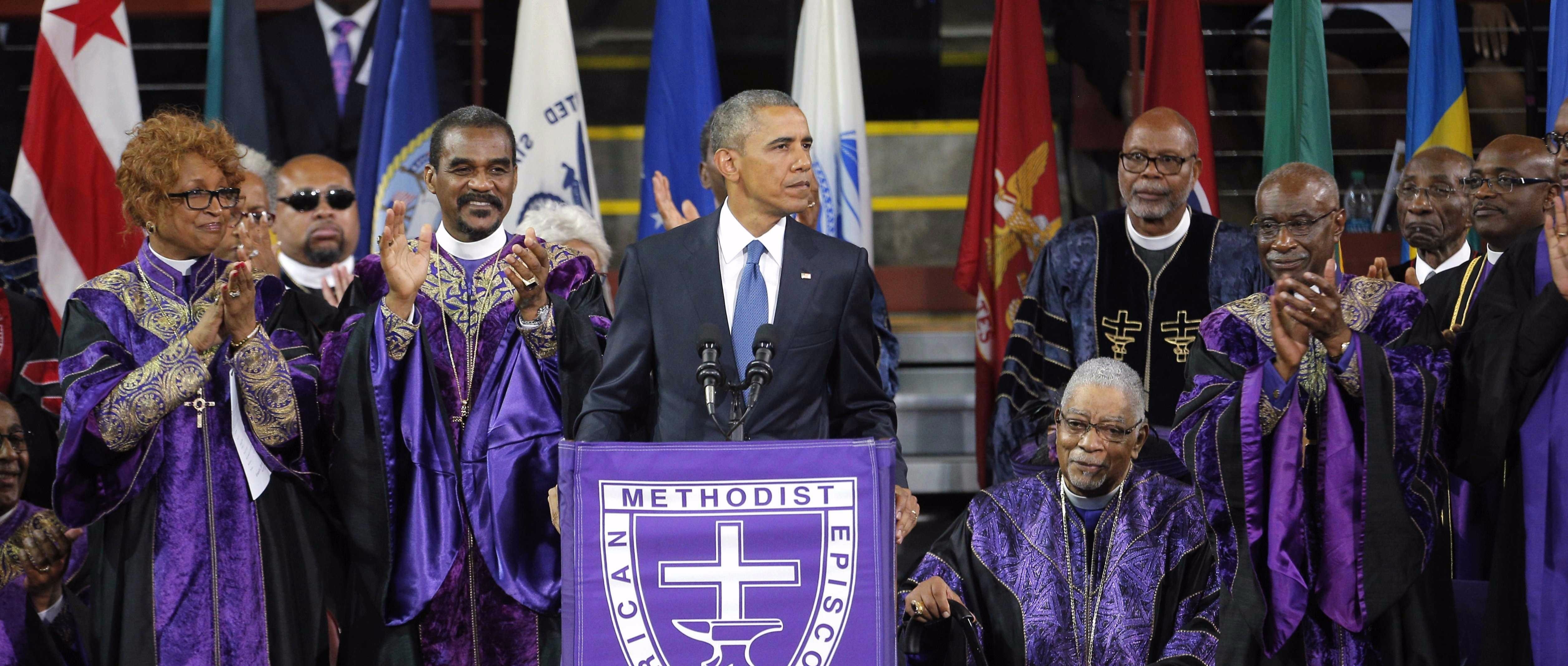

As Mother Emanuel’s choir sang ‘The Old Ship of Zion,’ a double-clapping Mr. Obama entered a sports arena-turned-sanctuary to honor Mr. Pinckney’s life, clearly feeling the weight of the moment. In the pulpit, the President gave a stirring rhetorical performance. He spoke of faith, perseverance and amazing grace. He reiterated a point he’d made in an interview earlier in the week, that racism isn’t just about racist relics or saying bad words. He spoke of the self-examination the moment requires of us all, the “honest accounting of America’s history.” His message’s gist was that the lasting effect of the Charleston Massacre cannot be limited to the eviction of the rebel flag, that the structures of racism must, too, topple with the bigot’s symbol.

“It would be a betrayal of everything Reverend Pinckney stood for,” he said, “if we allowed ourselves to slip into a comfortable silence again.”

The notion of our first black president eulogizing a black state senator assassinated in a hate crime straight out of the 1960s made for a poignant contrast.

Every time I think I could no more admire Mr. Obama than I do, I do. Nearly seven years ago, when he was elected, I saw a glimpse of what America’s promise looks like. But I never suffered any illusions that his election signaled every bigot’s cure or the vanishing of racism’s every vestige.

Quite the opposite happened, actually. Mr. Obama’s election, it’s fair to say, brought racial tensions to a head. If ever white supremacists and like-minded folks were to think their country was being taken away from them, his ascending to the presidency was their surest sign. And what makes Mr. Obama so impressive is that he seems keenly aware he represents the paradox of race in America, yet he never shrinks when race, our most contentious debate, is the topic du jour.

“I’m fearless,” said Mr. Obama recently, describing his mood at this point in his public career. That fearlessness was on display when he eulogized Mr. Pinckney. He was as frank and passionate about race as we’ve ever seen and rightfully so. Now well into the fourth quarter of his presidency, he’s likely providing a glimpse into his post-presidency work, which could be taking shape right before our eyes.

We can’t yet fully consider how Mr. Obama’s era has changed race relations in America. But as he finds his boldest voice on the issue, he positions himself to be efficacious on the issue and especially so should he use his post-presidential potential to wrestle racial injustice and inequality.

Mr. Obama still inspires hope in me. I’m not cynical about America. Its arc, from my perspective, bends toward justice. Removing racist symbols is important; it’s a worthy cause. The lowering of the rebel flag in Montgomery, Alabama, the first capital of the Confederacy, is massive, if tardy, symbolism. It’s another step towards a more perfect union. But we must not stop there.

In the wake of the Charleston Massacre, as Confederate emblems fall, the focus must now turn to removing systemic racism—to combating voter suppression, police brutality and poverty, to addressing the issue of dilapidated schools and lack of access to affordable and adequate health care.

Solving structural, systemic racism won’t be as easy as pulling halyard. But it’s fix is where transformative progress will be made. It’s the most fitting memorial for those nine worshippers.